The next cave I explored in Pang Ma Pha District in the province of Mae Hong Son was Tham Pakarang, Cave Coral in English, which is well known for its amazingly beautiful flowstone formation and other speleothems. I engaged the service of a local guide named Tientong who led me on a 4WD vehicle traveling 2.5 km on a dirt road from Mae Lana village to the “Tham Pakarang” signpost. We parked the car there and walked on a 100-meter path to the cave entrance and followed a stable wooden stairway built by the provincial administration 5 meter high down to the cave floor. Tientong briefed us that the cave was 948 m long and comprised 3 main chambers.

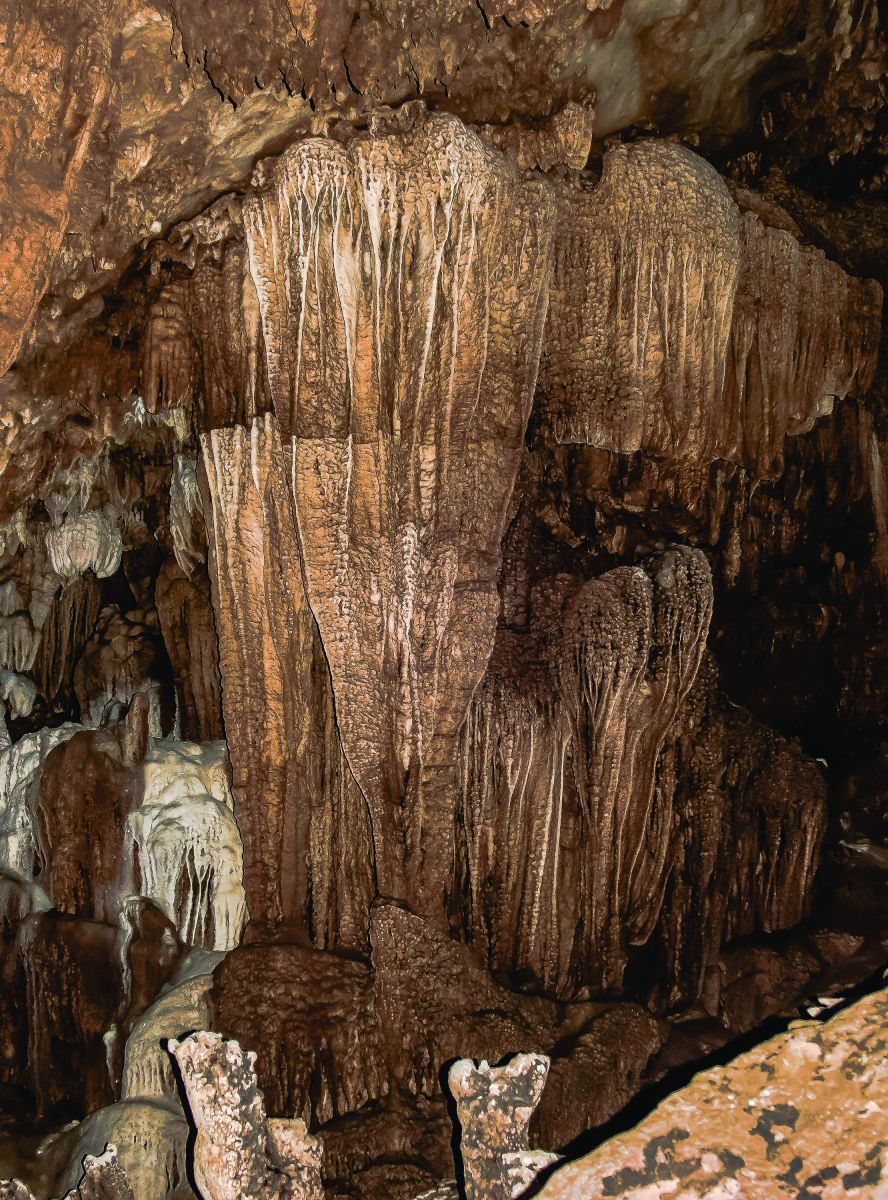

Tientong led us into Chamber #1, a spacious room with a very high ceiling. I shone my high-powered flashlight at a large wall of the chamber and stared in wonder at a continuous line of flowstone extending downward from the cave wall. The guide explained that a flowstone was originated from water flowing from outside through a crack of the cave wall streaming downward to the floor. The water which contained mostly calcite or other carbonate minerals evaporated away over time leaving a solid sheet of those minerals in the form of flowing water which became known as flowstone. The long line of flowstone appeared before us must have been created by water coming through several wide cracks on the cave wall.

Tientong directed his flashlight at the opposite wall showing a dominating image of several towering flowstone forming a huge wall reaching down to the cave floor. Spreading over a large area of the floor were many stalagmites, each about 1 to 2 feet high, several of which were still alive and growing. At one end of the chamber we found a section of false or fossil floor extending from a large flowstone about 4 m above the floor. It was a remain of the former floor of the cave which was corroded away throughout the years. It is called false floor or fossil floor and is also classified as a subtype of flowstone called canopy flowstone. Nearby on the same wall was another amazing flowstone cascade with long, deep streaks fanning out to form draperies, some of which showed bands of different colors looking like bacon strips coining the name “bacon draperies”.

We were led by Tientong walking down and up a continuous slope until we reached a flat wide area which Tientong called Chamber #2. The highlights of this chamber were beautifully developed soda straws and cone-shaped stalactites most of them were still active as indicated by water dropping from their ends onto the floor. After we’ve spent time photographing those speleothems, Tientong told us there were more highlights and took us to where we found several stalagmites which allowed us to express our creative imagination in naming each speleothem.

.jpg)

Two speleothems caught my eyes and immediately I said, “A crocodile and a sea lion”. A large fallen limestone column lying on the ground looked very much like a crocodile. Almost 2 meters away located another speleothem which my imagination told me that it could be a sea lion. We moved to a nearby speleothem comprising 3 standing stalagmites of different figures and sizes and tried to figure out what to call them. Tientong suddenly remarked, “They’re father, child, and mother”, which we all agreed to his elucidation.

Then I saw an eye-catching limestone figure near the wall and walked closer. “This is definitely a rhino horn,” I exclaimed. Silence followed as everyone agreed with my observation. “You’re right!” said Tientong, and continued, “What do you call these objects?” as he led us to a nearby single limestone rock about a meter high. There were 3 similar items on top of that rock. After a few seconds, I commented, “They look like fried eggs!” Tientong laughed softly and replied, “You’re right. They’re called fried egg stalagmites.” The guide added that they are in the early stage in the formation of stalagmites. However, it is doubtful whether they’ll grow into a large stalagmite because the rock on which all three of them are located is too small to become a solid base for them to grow any further.”

Tientong then led us to a cluster of stalagmites, each not more than 2 feet tall, and said, “Point out an owl for me.” We walked around those stalagmites scrutinizing each one closely and could not find one that resembled an owl. I finally cried out, “Impossible! There’s no stone that looks like an owl or even near it.”

“I’ll show you,” Tientong said with a smile on his face. He turned on his flashlight, walked to a particular small column, and shone the flashlight at that column. The light went through a crack on the column and suddenly a figure resembling an owl appeared on the cave wall 4 meters away.

“What a magic!” I exclaimed and couldn’t believe what I saw. “How could you find it?”

“It was a coincidence!” replied Tientong. “It was found by chance!”

We walked toward the rear of the chamber where a magnificent flowstone cascade in golden brown color appeared before us. I asked Tientong, “What cause those flowstone to be in this color?” The reply was, “The stream of water flowing continuously into the cave a very long time ago contained a large quantity of iron oxide. When the water evaporated, the remains were mostly iron oxide mineral which gave the flowstone the golden brown color we’re seeing now.”

“We’ll be entering Chamber # 3 which is the last chamber of the cave,” said Tientong. “The path will be narrower which will lead to the amazingly beautiful flowstone cascade and a garden of cave corals. You’ll see why this cave is named Tham Pakarang.”

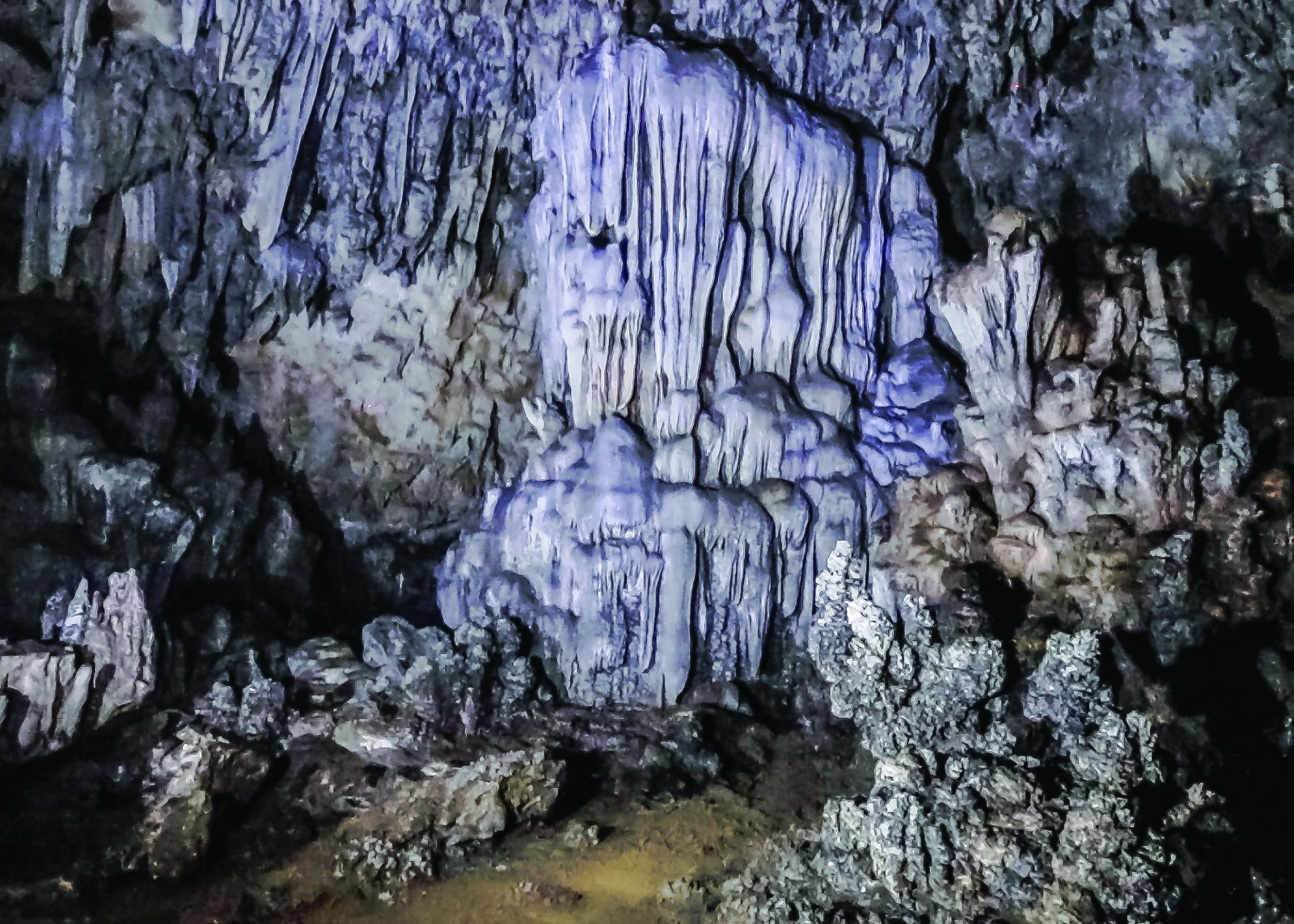

We followed Tientong along a corridor about 6 meters wide with high ceiling for 5 minutes. We suddenly found ourselves staring at an extraordinary sight in front of us. It looked as if we were about to enter an underwater world in a cave on a mountain 760 meters above sea level.

What caught our attention on a wide slope on the foreground was a cluster of stalagmites resembling real corals we saw when diving under the sea. Even a few stalagmites appearing on the slope in the shape of sea flowers looked very real. Beyond the coral garden we saw a wall of blue flowstone cascades dominating the scene behind which could easily convince us that we were actually in the deep blue sea. Seeing our reaction, Tientong commented, “Wait until you see the rest of this chamber. Follow me.”

Tientong led us walking a short distance through a narrow trail between the slope of corals and the blue flowstone cascades until we reached the end of the chamber. We all shone our flashlights at the awe-inspiring sight in front of us. It was a spectacular flowstone cascade in blue and tan color almost covering the whole wall. Scattering on top of the flowstone were crystal-liked white calcite flakes which we have not seen before in the other caves.

I left Tham Pakarang impressed by our discovery of the amazingly beautiful sights of speleothems. My adventures into Thai caves have become more meaningful and captivating as I was learning more and more about speleology, cave minerals, and cave animals from personal observation, books, websites, and videos on cave exploration. I’ve already ventured into 5 caves in Chiang Rai, 6 caves in Mae Hong Son, and recently 10 caves in Kanchanaburi and Rachaburi. I’m planning my next destination to explore sea caves in southern Thailand and also more limestone caves in northeastern Thailand.

However, I still have my commitment to narrate my adventure into one more cave in Mae Hong Son. It is Tham Pha Daeng or Cave Red Cliff in Pang Ma Pha District, which contains uniquely magnificent speleothems different from the other caves I’ve previously visited.

Until we meet again in the next issue of Elite Plus.