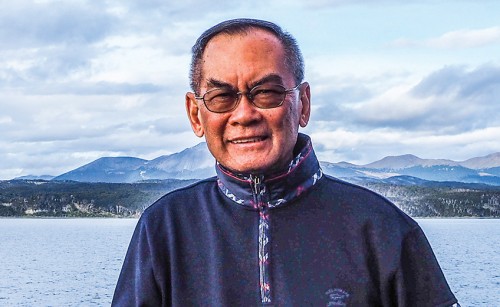

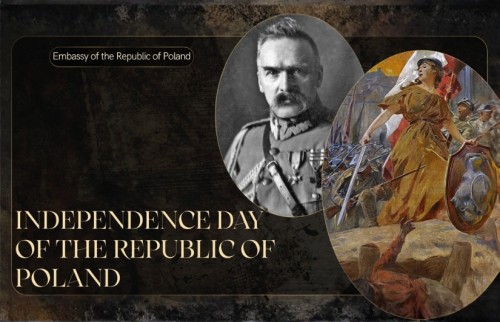

Photo by Jenny Chan

Germany is famous for its annual Oktoberfest beer festival in Munich where a feast of grilled pork sausages and meats with sauerkraut are consumed along with steins of beer. But is that all Germany has to offer? I sat down with HE Ambassador Schmidt to learn about Germany’s past and present food culture and how it has evolved over the years.

(3).jpg)

We began with Ambassador Schmidt sharing a brief history of German Cuisine. “In the early days, food was all about survival. Nature decided what people could eat. German food centred around wheat as a staple in the form of bread. Meat, whether raised in farms or hunted, was linked to wealth.

“German cuisine changed greatly due to the import of crops from other continents. The most significant example was the potato from Latin America. Slowly, but steadily, it ‘conquered’ Germany beginning in the 17th century and has now become an integral part of German food today.”

(6).jpg)

Ambassador Schmidt elaborated, “Potatoes became a staple crop during the reign of Frederick the Great. Due to the ongoing wars and strife, people were starving and under-nourished. Soldiers built their camps on the fields of existing crops. Harvests were destroyed. So potatoes, a root crop, which would not be easily destroyed, were grown instead. However, due to this root vegetable’s tastelessness, it was considered by many unsuitable for eating and was grown in botanical gardens. People remained unfamiliar with the tuber, and as the saying in German goes, ‘Was der Bauer nicht kennt, frisst er nicht’, which means, ‘What the farmer doesn’t know, he will not eat.’

.jpg)

“Frederick the Great then forged a cunning plan. He applied the ‘Psychology of Persuasion’ by banning the potato and ordering that they could only be grown on crown land. He next sent soldiers to guard the fields to stop farmers from stealing the yields. However, at the same time, the king told his troops to pretend to sleep and allow farmers to steal the potatoes. The saying, ‘Anything that is worth protecting is worth stealing,’ came true. The people became attracted to food of ‘royal quality’ and started to snaffle them for their own consumption. This story covers the beginning of the potato as one of the staple foods in Germany. Today, Germans are avid potato eaters, and it is hard to imagine German cuisine without it. Some visitors to Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam will leave a raw potato on the grave of Frederick the Great as a token of gratitude.”

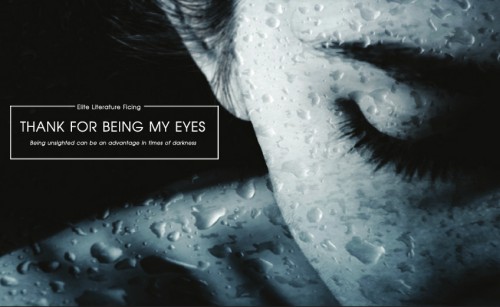

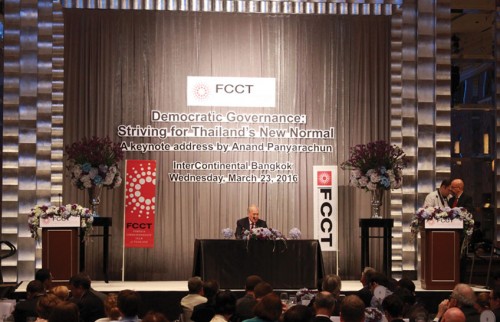

Ambassador Schmidt admitted that German food is not as popular globally as, for instance, Italian, Chinese or Thai cuisine. Many see German food as heavy and unrefined. Ambassador Schmidt explained, “If you look, you will see that German cakes and breads have spread into many countries. Additionally, German beer is known and liked all over the world - maybe the most successful of German food exports.”

Ambassador Schmidt went on, “In German we say, ‘Liebe geht durch den Magen’, which literally means, ‘Love goes through the stomach.’ Germans enjoy their food like people elsewhere. It is intricately linked to all important events in life. Religious and folk festivals as well as weddings and funerals all centre around food. Enjoying a meal together is at the essence of German ‘Gemütlichkeit’, comfort and cosiness. One world renowned food festival in Germany is the ‘Oktoberfest’. Lesser known festivities are the numerous celebrations around the harvesting of wine in the southern regions.”

.jpg)

“Given the strong links of German food with our neighbouring countries, you will always find many similar dishes. Sauerkraut is taken as ‘choucroute’ in France; sausages are also prevalent in Austria and Switzerland and the northern German fish dishes can also be found in the Netherlands and Denmark. Some German dishes have travelled the world; take the ‘pretzel’, originally from Bretzel, Germany.”

Ambassador Schmidt emphasized, “Seasonal changes influence food a lot. In spring, many Germans are very excited about ‘Spargelzeit’, white asparagus season. It even has an official ‘end day’, the 24th of June. Then comes the season for fresh strawberries, berries and stone fruits. Autumn is for tucking into pumpkins and gourds. This is also the season when freshly harvested wine - Neuer Süsser and Federweißer - hit the shelves. Freshness of ingredients is crucial for delicious German food.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

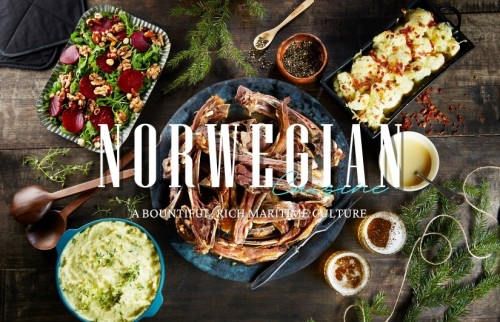

Traditionally, German food is a hot meal for lunch and cold meal for dinner, ‘Abendbrot’, translated as evening bread. A hot meal would consist of soup as a starter, a main course with meat or fish, vegetables paired with a salad and some sweets afterwards. The cold meal is rich in variety, including vegetables, cheeses, cold cuts and different types of bread. Many Germans also love their ‘Kaffeezeit’, a cup of coffee with a cake in the afternoon.

.jpg)

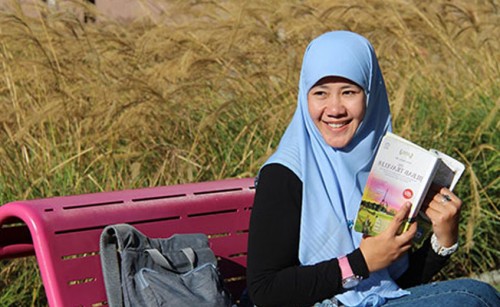

Ambassador Schmidt explained, “German cuisine draws its inspiration from everywhere. France and Italy have played a big role, as has Polish, Turkish and other Middle Eastern cooking traditions, to name but a few. In recent years, the Vietnamese community has made Asian food much more popular in Germany as well.”

When it comes to regional differences, Ambassador Schmidt said, “Geography is the main determining factor. Germany is such a regionally diverse country, relying on a bounty of beautiful, fresh, local products from its farms, forests and waters. Around Hamburg and in the northern coastal areas, fresh fish and seafood in all their varieties are much more common while the south puts meat at the centre of most meals, especially pork, beef and sausages. Many different sausages bear the name of a city such as ‘Nürnberger’ or ‘Frankfurter’.”

When traveling in Germany, it is good to ask for local specialties. A good example is Baden-Wuerttemberg in the southwest of Germany. Here, you will find a dish called ‘Maultaschen’, literally mouth bags, quite similar to ravioli. The filling of the pasta can be vegetables or meat. Legend has it that the locals hid meat inside so they could continue to eat meat even in the fasting period of Lent before Easter. The area bordering the North Sea, or Baltic Sea, is where you are most likely to enjoy seafood such as rollmops and herrings.”

.jpg)

“Cake is enjoyed nationally, but regional variations include ‘Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte’ from the Black Forest and the unusually named Bee Sting cake, ‘Bienenstich Kuchen’, from Andernach. One story tells that Andernach was under attack from its neighbouring village, Linz. Villagers threw bee-hives to thwart the attack. To celebrate, the victory cake was called ‘Bienenstich’. So, as you can see, when you explore Germany’s regions, in addition to delicious food, you often get a good story.”

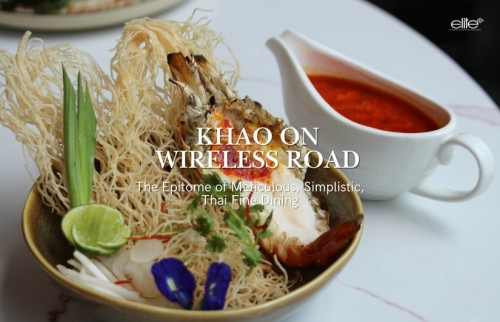

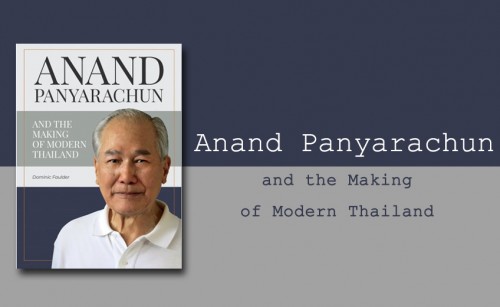

Key representative dishes

Ambassador Schmidt candidly pointed out that it would be hard to choose one dish that stands out without upsetting someone.

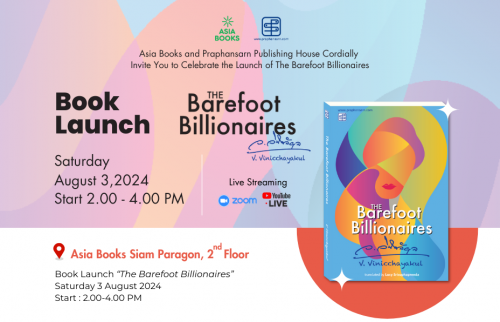

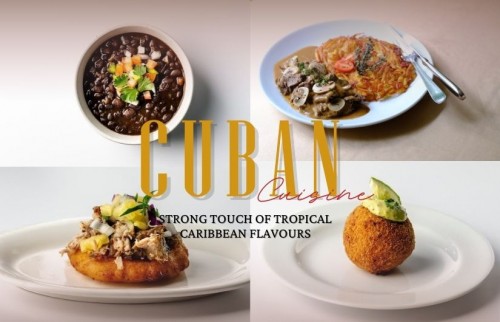

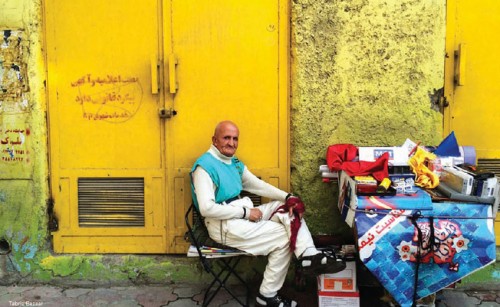

.jpg)

‘Currywurst’ is Berlin’s most famous food and a pride for many residents. It is actually considered street food, not a dish Germans eat at home. Its ‘cult status’ is clear by the fact that there is even a museum in its honour. The secret is in the sauce, a combination of the three key ingredients: ketchup, Worcestershire sauce and curry powder. Currywurst was born out of need. After the Second World War, a lady from Berlin was given some ingredients by British soldiers. She combined them and created this new taste that filled hungry stomachs in those difficult times.

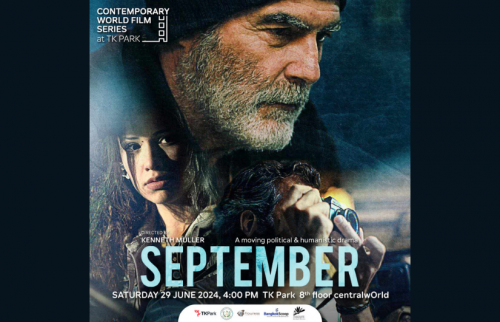

.jpg)

Another meaty favourite is ‘Schweinshaxe’, pork knuckle. They are usually quite big and well roasted until the skin is crispy and nearly falls off the bone, and the meat is tender and juicy. As famous as Oktoberfest and Bavarian “Lederhosen”, this dish is often served with potatoes and sauerkraut to be paired with beer or schnapps.

Germany is well known for its salads. They can consist of any combination of vegetables and come with different dressings. Any meal in a restaurant is served with a side salad. In addition, there are restaurants specializing in salads only.

.jpg)

In general, Germans enjoy hearty, home-cooked meals, especially the national and regional dishes we covered earlier. With the influx of foreigners in the more cosmopolitan cities, many foreign dishes such as Turkish, Italian, Thai, Chinese, French and Indian have been infused with an unusual German twist.

Turkish immigrants brought not only the Döner, but also many dips and wonderful sweets to the German table. Vietnamese immigrants added Pho and introduced fried sushi rolls. In addition, eating habits are changing as well. Schweinshaxe and sausages are being replaced more and more by vegetarian or vegan choices. The ‘German Ministry of Food and Agriculture 2020 Nutrition’ report stated that fruit and vegetables top the list of daily intakes. Dairy products and meats come in second and third place. Animal welfare and climate change considerations play an important role in food choices today.

As our interview drew to a close, Ambassador Schmidt concluded, “German food is constantly changing. Modern German chefs have started to create newer, lighter fare, incorporating traditional foods into their menus. Germans still fall hold to their rich heritage, serving wild game, lamb, pork and beef. Like in other countries, chefs are reinventing themselves, creating new experiences by embracing traditional ingredients such as mustard, horseradish and juniper berries with fresher, more cosmopolitan flavours.

“The food business is very competitive. If you want to go by the Michelin 2023 edition, Germany boasts an all-time high of 334 Michelin Star restaurants, including one more three star restaurant, the highest grade. Interestingly enough, many of the famous restaurants are not in the big cities but in the countryside. Federalism works for food. Visit and explore Germany and its cuisine - ‘Guten Appetit’!”

.jpg)