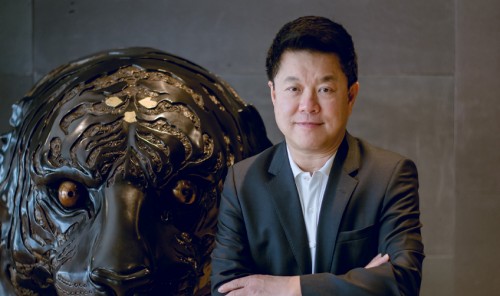

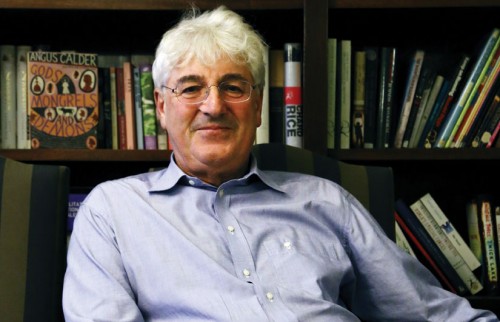

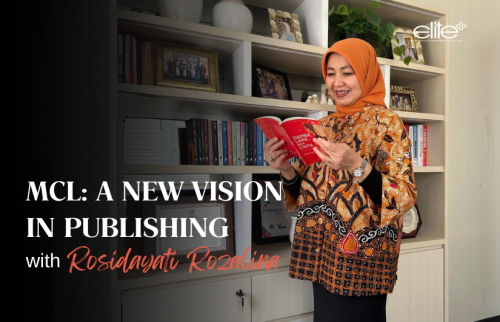

English is becoming more important as the world grows progressively interconnected, yet standards of English vary widely from country to country. Why are some countries good at English as a foreign language and others not? Elite+ went looking for answers from the best-selling educational writers in the world’s leading country at English education.

In October, Elite+ caught up with Andy Coombs and Sarah Schofield at their relaxing office space on the beautiful island of Saltsjö-Boo, a suburb of Stockholm, Sweden. Andy and Sarah run Polar Fish Publishing AB, an exciting new publishing house working with children’s fiction and ELT. They are the creative team behind Sweden’s “Good Stuff” series and the new “Idby” illustrated series for young readers.

In a country of less than 10 million people, over a million Good Stuff books have been sold. Sweden consistently ranks No 1 globally on foreign language indicators. So what makes Good Stuff so successful and what makes Sweden so successful in teaching English? We sat down in front of a roaring fire, with a pot of coffee and a plate of cakes and asked for some answers.

Please explain what Good Stuff is.

Andy : It’s a series of 20 schoolbooks plus audio CDs, interactive digital materials and exercises designed to teach English to Swedish students aged 11 to 16.

Sarah : We began in 2000 and it’s still going strong. We’ve just completed the new editions, entitled Good Stuff Gold. Is showing English as an international tool through complete narratives the secret to English learning?

Sarah : It’s a start, I think. Our books always have fact and fantasy, humour and depth. Life can be serious but it can also be funny. Students respond to both.

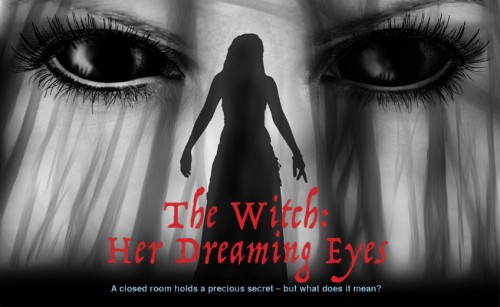

Andy : We work a lot on getting the balance of texts right; people have different interests. So we might have a spooky dialogue set in a deserted castle, a story about visiting a fun fair, a fact piece about raising sheep in New Zealand or even a joke about a parrot on a cruise ship, side by side. We keep to a narrative thread that pulls ideas and big questions together. The

What is the secret to your success in teaching English?

Sarah : When we started the coursebooks we focused on a couple of key areas. The first was the notion that content is king. Other ways of teaching English give students parts of stories or dialogue to read and study. The language is analyzed for structure and meaning. We didn’t just want to give them language, but ideas instead. We wanted a complete narrative to hook and stimulate the students’ curiosity and passion.

Andy : It’s natural when you think about it. We grow up with stories – a beginning, middle and end. It’s how we are wired. If you are interested in a story, you want to know how it ends. The student ends up wanting to improve their English to find out where the stories lead. Language needs to be in context. Language is a living tool for exploring ideas and communicating thoughts.

The books are very international with stories and characters from all over the world. Can you tell us a bit about that?

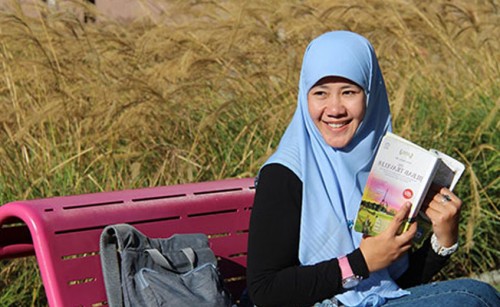

Sarah : We had a clear idea of how we wanted our readers and teachers to view English. Often when you open an English teaching book, you are presented with the idea that you are learning somebody else’s language. You are learning the language of the UK, USA and others. But we wanted to show that English is now an international tool.

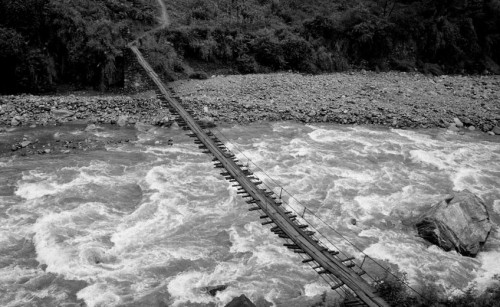

Andy : There are far more second-language speakers of English in the world than native speakers – maybe 5 to 1. So if we go by the numbers, English should be seen more as the tool of second language speakers than first-language speakers.

Sarah : English lets anyone engage with the world. Once you’ve got English you can trade with China, chat with Brazil and play games in France. And sure, you can order a pea fritter in a British fish-and-chips shop. But it’s not so important that you learn about red buses in London or yellow cabs in New York. So we focus on showing English as an international language, full of diversity and the potential to unlock access to a global conversation. Surely it’s just as important to learn how to respectfully greet a Chinese businessperson in English as it is to hail a cab in downtown Manhattan.

Is showing English as an international tool through complete narratives the secret to English learning?

Sarah : It’s a start, I think. Our books always have fact and fantasy, humour and depth. Life can be serious but it can also be funny. Students respond to both.

Andy : We work a lot on getting the balance of texts right; people have different interests. So we might have a spooky dialogue set in a deserted castle, a story about visiting a fun fair, a fact piece about raising sheep in New Zealand or even a joke about a parrot on a cruise ship, side by side. We keep to a narrative thread that pulls ideas and big questions together. The levels progress and offer a way to reach the students regardless of ability or passion.

Sarah : Passion or what students love is really important. It’s how you first gain their interest and how you maintain it through four or five years of education. We taught English around the world for years before writing these books. We noticed a worrying trend that came from the culture of teaching English. Most materials assume that if your language ability is low then in some way the concepts also need to be on a lower level. So a beginner learns about a cat sitting on a mat but a more advanced student talks about the environment or explores what qualities make a great friend. To us, this is completely wrong. Just because your language ability is low does not mean you are not interested in complex ideas.

Andy : So we wrote all of our texts with that in mind. For us, the more interesting the idea the more likely a student is to engage and pursue their learning. A teacher can only do so much. If the students are bored, they will not learn as quickly.

Sarah : Yes, we try to write to their curiosity: curiosity to learn new stuff, curiosity to see where a story is going and curiosity to explore opinions.

Andy : So everything we write comes from that position: keep the language simple but the ideas fascinating. Once a student realizes they can talk about complicated stuff in simple language, their confidence goes up; they don’t feel patronized, they feel engaged.

What did you have in mind when creating Idby?

Andy : We soon realized that by the time our students start reading Good Stuff at age 11 or 12, they are already trained in the false idea that simple language is connected to simple ideas. So we decided to create something to change that. Idby is the result.

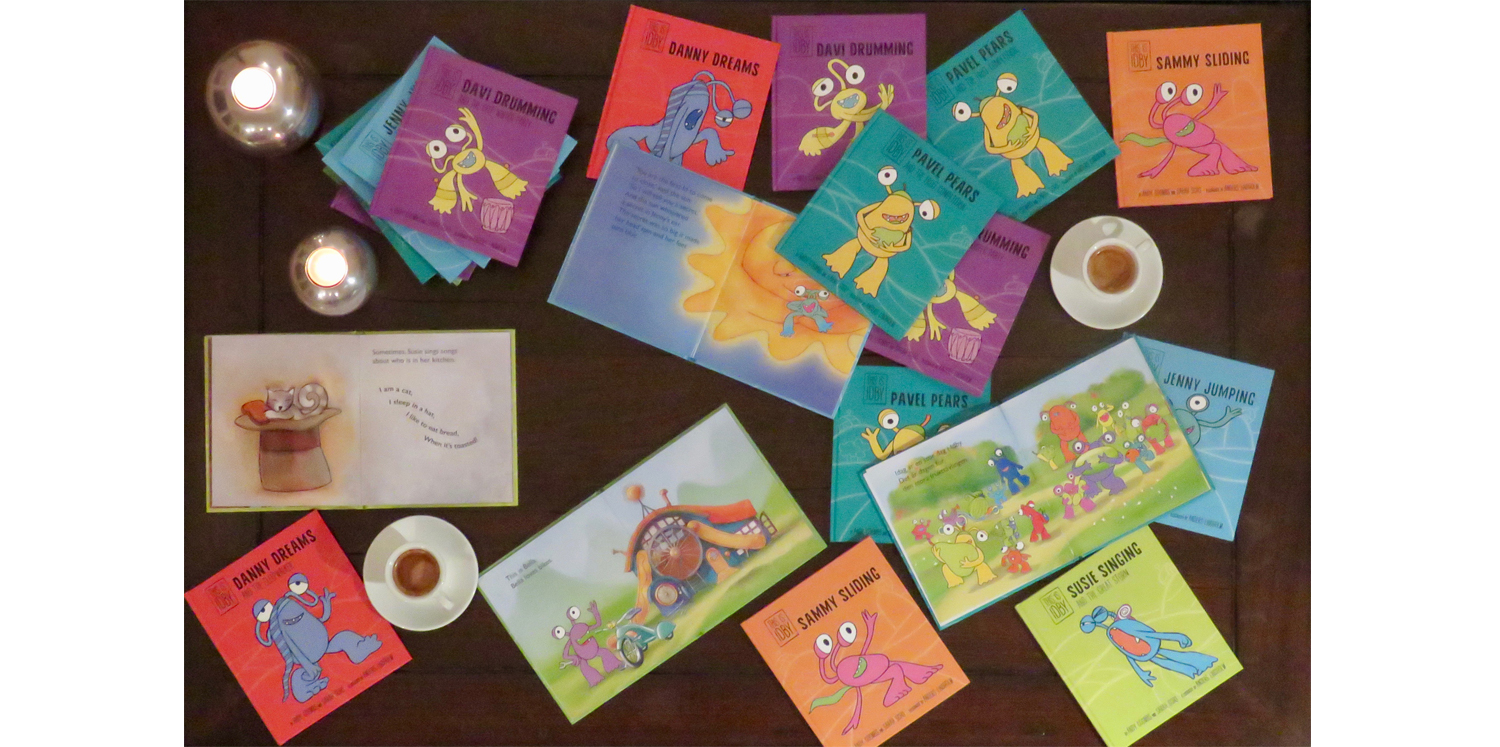

Sarah : The Idby stories are based around characters like Jenny Jumping and Danny Dreaming. Jenny Jumping loves jumping. She jumps everywhere! This is what defines her. Not whether she comes from Asia or Europe. Not if she is a boy or a girl or old or young or fat or thin. Who Jenny is, what Jenny is all about, is what she loves. It’s the “personality first” approach to character.

And do you stick to the simple language, complex ideas way of writing?

Sarah : Absolutely. The stories are told in very simple language but we explore time travel, dreams, space travel…

Andy : And sometimes we just explore splashing with frogs, playing football, making a sandcastle or eating birthday cake in an underground kingdom with moles.

Sarah : When very young readers get into a complicated idea they go with it. It’s amazing to watch a four-year-old thinking about time travel. If the language is right, any idea is possible.

Andy : We do get a bit sidetracked with designing card games, puzzle books, posters and T-shirts, but the heart of what we do is still the stories. Right now we have 16 books published. But we are in the process of developing the series to a total of 48 books over the next two years or so.

In this digital era, there’s an idea that people don’t really read books. What’s the future of printed books and how do you, as a publisher, adapt to this change?

Andy : As you know, Sweden is a highly developed, technological society. All schools have access to fast internet and most students will work with tablets or laptops.

Sarah : We have just completed a two-year project with the Swedish National Encyclopedia creating a purely digital English language course.

Andy : And we actually started out as a digital publisher. We created stories and education just to be used online. We spent three years looking at how digital materials were being used in schools and we learned a lot. Digital has advantages but also disadvantages.

Sarah : There advantages to digital in terms of cost, distribution and the environment – but the most up-to-date studies show the reading experience seems to be better on paper. In fact, some places are now replacing their computers and laptops with printed books.

Andy : Twenty years ago the assumption was “if it’s digital, it’s better”. With technology you can do lots of things. When we watched how children read, we found that with highly interactive digital books they immediately start pressing the screen trying to fi nd what pictures move or make sounds and the story becomes less important. By adding more and more levels of interactivity the story turns from a narrative experience into a gaming experience. Sometimes adding stuff takes away from what is really important.

Sarah : And I think how we adapt is by keeping an open mind. I think publishers need to research and refl ect and not always rush towards the newest thing. It’s tempting to make something interactive just because you can. Now when we create a digital product it’s more about trying to keep it as simple as possible. You need students engaging with each other and with the teacher and not just looking at a screen. So doing everything digitally is not so effective. Print has strengths and advantages and so does digital.

Andy : The challenge for modern publishers and educators is to fi nd the best way to use both.

For more information, please visit www.polarfi sh.se.

English learning secrets from Sweden

- Present English as an international tool for everyone.

- Read complete stories not samples.

- Explore complex ideas in simple language.

- Enjoy a wide range of genres and styles.

- English is serious and funny. Profound and light. Experience all of it.

- Teach personality fi rst.

Personality first

Personality first is a social-philosophical approach to character definition in story, film, education and broader culture. It is typified by two basic ideas: it is always good to challenge stereotypes and a character should be defined by what they think and feel rather than gender, ethnicity, age, body type and ability.