You won’t meet a more humble pop star than Agnes Chan. The petite Hong Kong native with a big heart has made as much of a career out of doing good deeds as she has from hit singles. The 61-year-old, who rose to prominence as a teenager in the 1970s, has dedicated her life to education and volunteer work, while continuing to perform. After achieving fame as a singer, Chan earned a PhD in child psychology from Stanford University, and became an accomplished essayist and novelist.

Her big break came at the age of 14. A cover of Joni Mitchell’s The Circle Game, sung with her older sister, was life-changing. Next came starring roles under revered Hong Kong director Chang Cheh, and a recording career in Japan, where Chan’s non-fluent Japanese and nymphean features turned her into a teenage idol.

Over the years, she balanced volunteer work, academics and entertainment. Her first concert in China was a benefit for revolutionary wife Soong Ching-ling’s children’s fund, drawing a crowd of 54,000. A 1984 visit to Ethiopia during a famine aired on Nippon TV, raising awareness of the despairing realities in Africa’s poorest countries.

Chan, the “pop star with a PhD” as the media often refers to her, is a strong, down-to-earth advocate of women’s and children’s rights. In 1998, Japan’s UNICEF committee named Chan its first goodwill ambassador, and since last year she has acted as the organization’s regional ambassador for East Asia and the Pacific.

She has made history deliberately – for example by convincing Japanese lawmakers to pass a law prohibiting Japanese men from hiring prostitutes under 18, even outside of Japan – and also unintentionally, as a breast cancer survivor. In 1989 she sparked a national debate in Japan about women in the workplace, after bringing her newborn son to the dressing room before a TV appearance.

Though she is busy as an ambassador, singer, TV presenter, writer and professor, the mother of three still enjoys everyday of life by working hard and keeping a positive attitude. In an exclusive interview with Elite+ from her office in Shibuya, Japan, she spoke about her passion for life and humanitarian issues.

Your songs have been popular for more than four decades across Asia. What makes you so popular?

I don’t know. [Back then] I was just a schoolgirl. I just sang my song and everybody liked it, maybe because I was young and my audience was also young so we had a lot in common, like how we feel about the world. I guess that’s how people related to me like a sister, like a friend, like a girl next door.

At 17, did you know anything about Japanese language or culture? What made you decide to move?

One thing was my curiosity about Japan. I wanted to find out what kind of country it is. And I didn’t know why I became popular in Hong Kong and Asia. I thought if I came to Japan and didn’t get popular, then it was probably luck. But if I got popular in Japan too, there must be something – maybe my singing or my look or something about me. So I chose to come here and my first song became a big hit here, too. Have you ever heard my Japanese debut song Hinageshi no Hana? I don’t even think it’s a good song but it became so popular. I don’t have to know the reason. I just try to be natural and be myself.

Why Japan?

Japan is a big market. and you need a lot of time to be here because the contract is six months and then I go home for two months and then I come back to sing for six months. So basically I spent more time in Japan after that and less time at home.

You were always busy with your career. What made you pursue a PhD?

I studied at Sophia University. It’s a good university but my father said I should go and think about my life. So I went to Canada and got my undergraduate degree from the University of Toronto and then I came back to sing again. The PhD [came] after I got married and had my first child. I was breastfeeding him so I brought him to work and this was the biggest family controversy in Japanese history, called the “Agnes controversy”.

They were saying that if you are a woman, you get married, you stay home and take care of your child and your husband. I brought my child to work instead. It’s not permissible. We have to give more rights to women, give more rights to working mothers, we have to allow woman to go back to work after they give birth and give women and men equal chances in the workplace. It became a big controversy. Some people said Agnes did a good thing, some said she did a bad thing, and a professor from Stanford University approached me and said why don’t you come back to school and learn about gender studies, education, economics and see the world, then you will understand why there is a controversy.

With the interest in feminist issues, why did you join UNICEF?

It doesn’t work if you talk about children and you don’t talk about women, because if we don’t help the mothers, we cannot help the children. Most of the time at UNICEF, we help the mothers, we educate and empower them and try to convince fathers to be responsible and take care of the family, then that family will be good for the child.

What made you become an activist?

I think my initiation was when I was in Hong Kong trying to help children, new immigrants from China or children who didn’t have parents or were physically challenged. I’m not from a rich family but there are many children in worse situations. I started to care about children at that age and then I went to Africa in 1985. There was a charity programme in Japan, and that year they decided to help the children in Ethiopia, when they had a drought and civil war millions of children were dying. They chose me to be the main personality and I asked them to send me to Africa, and they said, “We can’t send you because of the war and sickness. You will die there.” But I said, “I can’t go on TV and say I’ve never seen them. I have to go.” I challenged them, and they finally let me go. That was the first time I went to Africa.

It was devastating. The children were starving and many died before my eyes. I realized the world is much larger than I thought and there are a lot of children that need our help. After that, I became very active for children. In 1998, UNICEF asked me to be their ambassador and I became more involved because there are so many children’s issues child prostitution, child pornography, child labour, child soldiers, trafficking, poverty, sickness. It’s like a never ending story. Hopefully we can give it a better ending. It’s been nearly 20 years since I became an ambassador. I’ve learned a lot.

You travel around Asia as well. What do children in Asia have in common?

When you talk about Asia, I think there is a rich Asia and there is an impoverished Asia. Especially in India, Bangladesh and some places in Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, even in Bhutan, Fiji, Papua New Guinea. But there are also rich countries like Thailand, Hong Kong or parts of China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia. In Asia we can help ourselves and at the same time I want the world to know more about where they can help. I want the richer countries to understand there are countries in Africa or in the Middle East that we can help. I want to be the bridge between people to help them understand the different types of problems for children around the world.

copy_1285836536.jpg)

So you don’t focus on Japan.

Right, because Japan is a donor country, not a recipient. What I do every year is travel to different countries, then I do my advocacy in Japan and raise funds. Japan doesn’t receive aid except when we have a big earthquake. We are one of the biggest donors. We are very active.

What countries do you focus on?

Mostly countries that are in war and poverty, usually in Africa and Asia. Recently I went to the Middle East to see the Syrian refugees. We focus on areas where there are children in need.

What touched you most in your 20 years as ambassador?

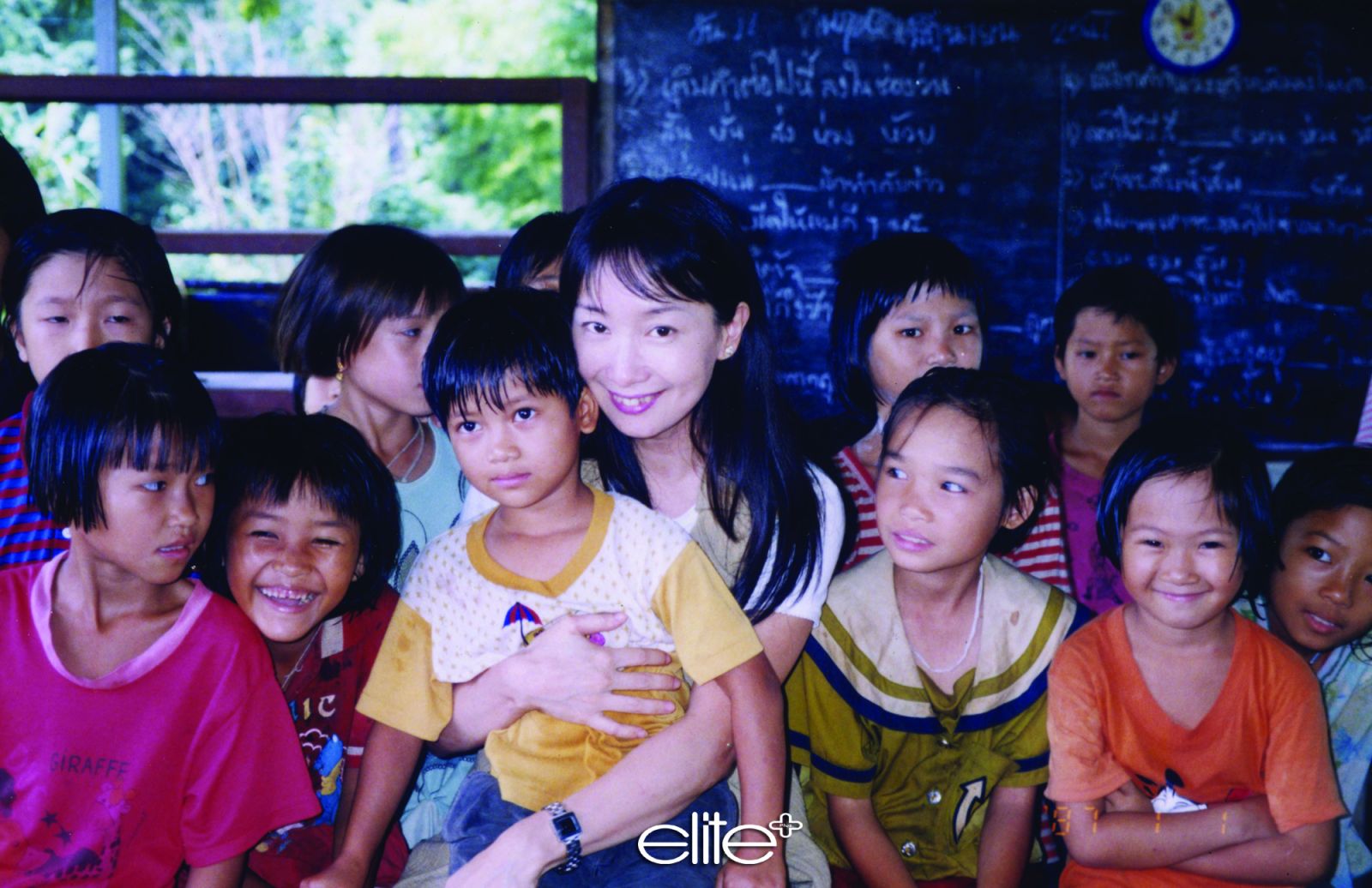

So many stories. Actually my first assignment was to go to Thailand. I went to Chiang Mai and Bangkok. Child prostitution was a problem in Thailand 20 years ago. There were men from other countries coming to buy children. Girls would be trafficked because Thailand is a big country with lots of tourists, so children from other countries like Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar got trafficked to Thailand. I went there to look at the problem. It changed my life. I met with a lot of victims that the police had already helped to get out. The young girls were traumatized. They hated themselves because they were forced to do something they felt was shameful. They didn’t want to be touched, they cried all the time, many tried to kill themselves. I said, “To me you are like a newborn baby. Things that people did to you don’t matter. You have no scars and you are like an angel to me and I love you and you have to love yourself. Forget about all the bad things, just think about the good.” I asked them to close their eyes and think about what they like to do most, and they would say, “I like to go to the mountains and sing.” Sometimes they would say “when I’m eating with my mother”. And I said, “Just keep that in your mind; all the bad things don’t touch you, forget about them.”

They were very strong, they taught me that I have to be stronger to help children. So Thailand gave me a lot of strength. When I came back, with other activists we were able to push through a law in Japan that prohibited child prostitution and child pornography. I became an ambassador in 1998, I learned about the problems and I did a lot of lobbying and in 1999 the law passed. It helped me to grow up. UNICEF told me the children are not pitiful; you should feel that they have human rights but their rights are infringed upon because we didn’t do our job. What we are doing is not because we feel sorry for them; we have to restore their rights.

So you’re doing your responsibility as an adult. That’s how the Thai children gave me the courage to face up to parliament. A lot of people hated me because I said no to child pornography, no to child prostitution, and bashed me on the internet, but I was not afraid because the children gave me courage. They’ve been to hell but they are still trying very hard. I keep doing what I’m supposed to do, because I want to bring the smiles back to the children. And as long as they are happy, I’m happy.

What challenges do children around Asia face?

Basically it’s poverty, especially in countries like Cambodia and Myanmar. They still traffic children, not only girls but boys too. And child labour is a big problem. They still use a lot of children to work, for example in the Philippines, which also has a problem of child prostitution. They have a lot of malnutrition, and if you are malnourished at the beginning of your life, you will not perform well at school and will drop out and can’t get a good job. It’s like a poverty cycle.

We want children to be well nourished, especially when the mother is pregnant and for the first 1,000 days. We want to make sure they have enough food, nourishment and when the children are born we want to make sure they have breast milk. We want to make sure they have good meals and the stimulus and education they need. And after three years, if they are well nourished and well brought up, it’s easier for them when they are going to kindergarten and primary school. But the first 1,000 days are crucial.

What are some solutions for these problems?

Every country is a little different. Some countries still believe that children are a kind of asset or income, so we have to convince the mother or father at least to let them go to school half a day and stop working. In some countries, they want their children to marry early, then the children drop out of school and marry at 13 or 14. When they get married, they may get physically abused, they may have to do all the housework, their life could be in danger.

We have to tackle the customs, education problems and poverty. It is long-term work but we have been doing it for a long time and we have lowered the fatality rate of children in the whole world, not only in Asia. When I became the ambassador, every year 13 million children died before the age of 5, now the number is 5.8 million. So we have cut the amount of death by half and we can do even better. The improvement is in Thailand but also Cambodia, Myanmar, and one of the biggest improvements is in China. Now they can feed themselves. Many of the children are in school and have nine years of schooling, so China has come a long way.

Asia has improved a lot but we don’t want any child to be left behind. We are focusing on children that are hardest to reach, like children living in mountain areas or [urban] poverty because in the big cities we have slums, we have children really in need.

Education can change people’s lives?

We believe that it gives them a chance to increase their self esteem and find a better job, to understand their rights so they can protect themselves and their children. We have to convince parents that girls are important, because one more year of education for the mother correlates to a healthier baby and better educated child. Every girl you educate, you have a big return because you get a healthier baby, a happier family, and family income increases.

What are your goals, and how many more years do you plan to work with UNICEF?

New problems always come out and we have to keep on doing prevention, feeding the children, helping mothers. There is a lot of chronic malnutrition. You don’t always see it but it’s there. For example, we thought that Guatemalans are small because of their genes, then we found a lot of Guatemalans in America are big and normal. We found out it’s the diet and malnutrition. The children are stunted. Their height is only about two-thirds, so even as an adult they are short. They have a lot of problems – they may die early, have complications, diseases, the brain doesn’t develop. So we are trying to educate them.

The more we know, the more new goals we have. My final goal is to put a smile on every child and hope they can stay alive, especially those living in war zones. I hope they have enough to eat and can go to school and have a dream, and when they grow up they can make their dream come true.

Have you ever felt like giving up?

Usually I get empowered when I visit children. When you go there, you see all the problems. For example, when I went to Qatar, the Palestinians were not allowed to go out of that area, so basically they are in a big prison. There is no electricity, no water, it’s unsafe, they are always attacked. They can’t go out so they marry each other, and big problems occur when you marry your relatives. Diseases like not hearing very well, not seeing very well are starting to come up among children. I visited a class when we were testing the hearing of children. I told them a story and said, “Today I’m going to give you homework. Go home and hug your mom and dad and say I love you.” They say they don’t know how to do it, and I say okay let’s practise. And the children come up and hug me and say I love you and we hold them. It’s the best thing in the world. They give me the love and courage to go on. It happened to us in Syria, too. After they hug me, the children start to walk around the room and hug everybody. The man who drove us around said, “Ambassador, I think if you give love to children, it multiplies.” What he said is correct. We can give love to children and it multiplies and the world will be a better place. I really believe that.

You meet underprivileged children around the world; how do you teach your three children?

I have three boys. They are big now. I teach them that they are very privileged, so they should do good because there is a reason they were born privileged – to help other people. You have to treasure your life and if there is an opportunity to do something, you should always try to do your best for yourself and for others.

Sometimes when I get tired and I complain, my son will say, “Oh, you have enough food to eat. Now you can go home and take a bath.” And I say, “I’m sorry. I’m not tired.” They come with me on trips and they also go by themselves to Cambodia, to Thailand, to other places to do volunteer work. So they don’t really complain. Sometimes when I complain about small things, they remind me, “Mom, you can’t complain.”

Have you used music to advocate on these issues as well?

Yes, basically through my music I try to advocate peace, because the worst situation for children is war. When there is conflict and fighting, lots of children die and even after war stops, the children don’t stop dying because a country needs a long time to recover. If you want to save children, peace is the basic thing you must have. I try to sing about peace, love, understanding and the treasure of life and the horror of war.

People often lack gratitude or awareness of what’s going on around them. How do you encourage people to be more compassionate?

I just try to talk to as many people as I can. I write, I sing, I go on TV and I talk. I trust that people basically are kind. Everybody must have like a piece of crystal that is transparent and pure in their heart. Everybody must have that when they are born but sometimes they forget because they are so busy.

When they hear stories about these children and how they suffer, they feel something and that little piece of crystal is talking to them. I believe that when they understand the situation and when the chance comes, they will do something about it. If there is an atmosphere of caring, something good will happen.

In Japan, that’s quite successful. We have lots of members who donate regularly and I think it’s because they really care for the children. No matter where you live, you can always do good. Even if you are sick, you can still do something good. For example, the nurse is coming and you smile to her and say, “You look nice today.” This is already helping.

Everybody can love somebody, because love is free. We have the right to be loved. We can love people and it is the biggest power hugging people, loving people, kissing people. Nobody can take this power away from us. If we want to love people, we can always do it. It’s the biggest gift we have. If people recognize that, there are all kinds of ways they can show their love.

copy_69973646.jpg)