Not many tourists visit Taunggyi, the capital of Shan State in Myanmar. Yet it is less than 50 minutes by car (30 kilometers) from Nyaungshwe, the town tourists must visit if only briefly when they go to Lake Inle.

A few resplendent pagodas, a couple of old churches, a cultural museum and a host of clothing shops may not offer a whole lot of reason for foreigners to visit Taunggyi. But a drive up to the ridge overlooking the city does lead to a south-facing viewpoint that overlooks the Awayyar Fire Balloon Field some 200 meters below, and a panoramic view over the Southern Shan Highlands.

A city of at least 150,000 people, Taunggyi sits at around 1400 meters in elevation on a relatively level spur of a north-south ridge that reaches more than 1700 meters at its highest point. To the south, this ridge bounds the east shore of Inle Lake.

At 880 meters in elevation, Lake Inle is a wonder. Most visitors will spend 2-3 days visiting this wondrous watery habitat of the Inta people before taking land tours to nearby places like Pindaya Cave, the Kakku Pagoda, the old hill station of Kalaw or hill folk villages in nearby highlands. None of these destinations require passing through Taunggyi, however.

Originally an upland Shan village, the site of Taunggyi was chosen as a military and administrative center by the British in 1894. Presumably it was also the British who tolerated if not encouraged the fire balloon festival. During Tazaungdaing, when Shan folk send hot air balloons into the night around the time of the full moon of the eighth Burmese lunar month to mark the end of Buddhist Lent , the festivities at Taunggyi have taken extraordinary form. The city stands out for its Fire Balloon Festival.

Assuming tourism is resurgent, and the festival takes place as scheduled in the last two weeks of November this year (2020), visitors who are going to Inle should definitely consider joining the festivities. Not to rent a car from Heho Airport (yomacarshare.com) or take a taxi from Nyaungshwe and go would be like taking a boat on Inle but not visiting any of the temples on the lake.

But the festival has two downsides. Primarily, it is dangerous, especially if you enjoy photography and want to get in close.

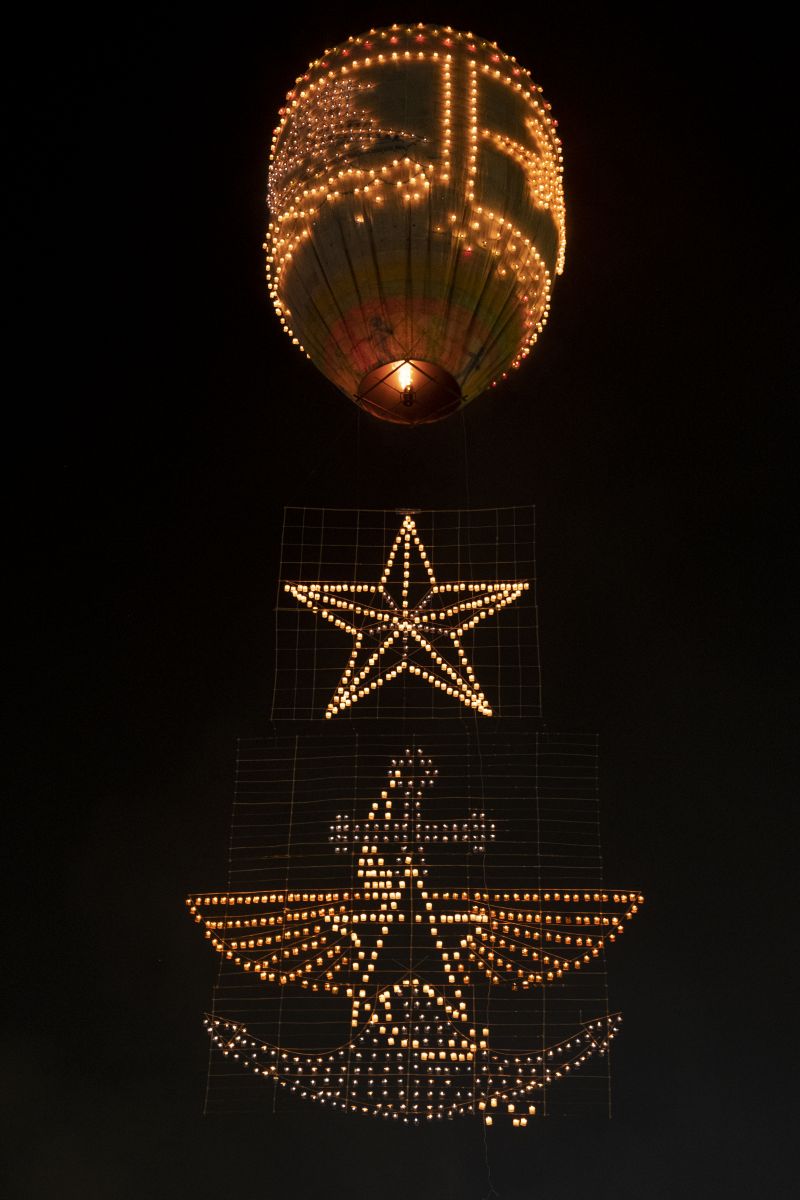

Made of a heavy cardboard-like paper, the balloons are 4-7 meters in height, much bigger than anything sent aloft in Northern Thailand during Loi Krathong or in Chiang Tung (Kengtung) during Tazaungdaing. Powered by multi-pronged wicks soaked in kerosene as tall as a man, the balloons are designed to lift payloads.

There are of two types of balloon and payload. The first and rather more gentle variety consists of the balloon, to which, as it is inflated, dozens of people frantically attach lanterns that swing on bamboo hinges, forming illuminated symbols on the rising outer skin of the balloon as it fills out. Once inflated, the balloon with its burning lanterns is held down until enough heat has built up to lift the payload. There are some with a bamboo framework forming a tail usually several meters long on which many more burning lanterns depict another symbolic shape as it upends and hangs vertically beneath the rising balloon.

The coordination among balloon teams consisting of up to a hundred members is something to admire; once the balloon is aloft, everyone in the team begins to jump, dance and shout with joy, watching as their balloon rises high and floats away.

The festival goes on for at least ten nights. The complexity of the launch effort means that each launch can take 30-minutes or more, the launch sequence presided over by the silver-haired field master flanked by the fire chief. Launches start in the evening and go on till the small hours of the morning, so perhaps around 15-20 balloons may be launched per night.

Naturally it is a competition, and the many thousands of dollars that each balloon costs can only be borne by organizations like village groups, institutions and companies. How the judges decide which team and balloon makes the best launch and show is hard to determine, for visitors will catch their breath each time a balloon rises.

The Awayyar fire balloon field is packed with people, many sitting on mats, snacking on treats hawked by vendors. On the fringes of the field are marquees containing discos, bars and restaurants. A fun fair has giant swings. Approaching the field from downtown Taunggyi requires walking up a long, wide alley lined with stalls, many selling warm clothing to fend off cold-season chill. You can buy a leather jacket for little more than 10 US dollars.

The crowds are dense; you may be jostling among groups of excited Shan folk as you walk toward the launch field. But you must be especially wary! When I went to report a lost wallet (most likely picked from my pocket — luckily there was not much in it) very early in the morning after my second visit to the festival, two dispirited Singaporean couples were telling the duty officer that cutpurses had slit the women’s bags and taken their phones, passports and wallets.

At the fire balloon field, you must be careful where to go. It is best to first observe a launch from a distance and see which direction the rising balloon floats—do not go anywhere within a wide arc downwind of a launch! But that is no guarantee as I was to find out.

The second type of balloon consists of a balloon envelope decorated with print—no lanterns attached. These are illuminated by searchlights as they begin to ascend. Beneath them is the payload. This consists of stacked racks of tightly packed, custom-made fireworks forming a cradle. It takes at least six men to lift these cradles. When all goes well, these balloons will delight all, emitting continuous showers of fireworks high in the night sky for many minutes.

But here’s the thing. As the fire balloon and the cradle below become buoyant and ready to rise, the team captain must decide when to light the fuses and release. If the fuses are too quick, the cradle too heavy or the rise of the balloon too slow, the balloon will be too low when fireworks on the cradle’s lowest layer ignite and spew forth. Those who have unwisely lingered too close can find themselves in a shower of burning phosphors.

And even if you are what you think is a decent distance upwind, the contrary can happen. The balloon you see in the photograph that was too close to the ground when its fireworks began igniting perversely floated about 100 degrees of arc away from expected downwind direction. It passed almost directly overhead. I had no cover. Phosphors were landing all around. One bounced off my camera, burned a fist-sized hole in my synthetic jacket and shirt, holing my cotton vest before dropping to the ground. Miraculously, it didn’t burn my skin, but my upper clothing was ruined.

On another launch, the cradle stays gave way, but fortunately the fiery mass crashed into empty ground beyond the field’s perimeter. On other nights, people have not been so lucky. Don’t wait till you see local folks running!