“Let there be an opening into the quiet that lies beneath the chaos, where you find the peace you did not think possible and see what shimmers within the storm.” - John O'Donohue

.jpg)

I walk out of the old gate lodge, closing its green front door with its brass knocker and double lock, into a front yard too small for anything but a few shrubs bordering a low dry-stone wall, and out onto the country lane. I imagine I am breathing Ireland’s cool air that is largely devoid of micro-particulate matter, but in reality it is the foul air of Chiang Mai during the hot season that envelops me.

I can only walk out of that lodge in my mind while the Covid-19 pandemic keeps me to my home in Doi Saket. The big plus for the planet is that I will not be contributing to a plume of carbon particulates like those embedded in the contrails from US and EU-bound jets that in normal times would be crossing the skies high above that lodge in County Cork.

That distant home came not by birth but by the fortuitous marriage of a sibling. No ancestry do I have that would give me claim to one of Ireland’s coveted green passports. I feel cursed as an Englishman in the time of Brexit, though I feel lucky not to be confined by Covid-19 on that maddeningly crowded isle of my birth. And yet, despite my national forbears having tramped for centuries over Irish aspirations for independence, the Irish welcome would always begin when a friendly immigration officer scanned my British passport upon arrival.

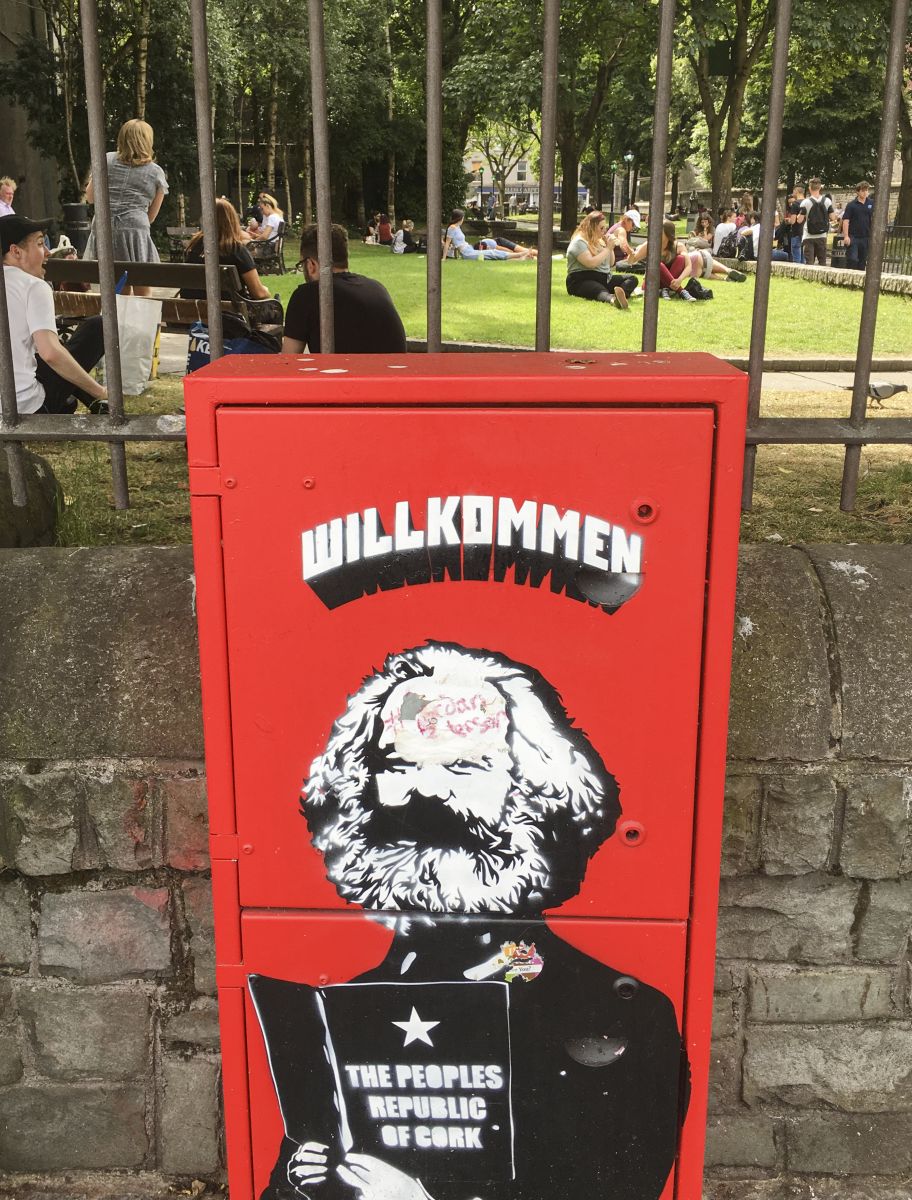

Céad míle Fáilte— welcome! Carved on a stone plaque, the sign greets me when I walk out of the lodge and turn left to cross the river into the village. Such signs seem like a defiant stand of the native tongue, whose majority Irish speaking populations have been reduced to small gaeltachtai in the far flung reaches of Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way.

When I turn right on the lane, I go up a hill and past the village school. There, despite the frustrations of many parents who bemoan a perceived waste of precious class hours, all children must study the Irish language in accordance with national policy. A grudging respect has to be given to the government for their dogged persistence to preserve Irish, even if its most prominent use to non-Irish speakers appears on the nation’s bilingual traffic signs.

The language of the Gaels, the last of the Celtic tribes to invade the island in the 3rd century B.C.E, successfully withstood the steady English inroads into the eastern parts of the island that began with Norman and Welsh barons taking control of lands in the southeast in the 12th century. Indeed, it was the Irish culture and language that absorbed the newcomers rather than the reverse.

However, in 1641, the landed Catholic gentry who yet owned 60 percent of the island rebelled against the growing writ of England, a rebellion that eventually brought the hated Oliver Cromwell and his parliamentarian army to Ireland. From 1649, Cromwell’s forces brutally suppressed the Catholic population. Within four years, famine, disease, war and deportation had reduced their numbers by an estimated 200,000-600,000 people.

By 1776, only around five percent of land remained in Irish hands due to a century of England’s restrictive plantation policy. Gaelic society was collapsing and decades of future Irish emigration gathering pace. Yet despite suppression and consequent misfortune, Irish remained the majority spoken language and was widely used in legal and commercial matters during the early 19th century.

My walk along the country lanes takes me past a road junction with a small stone memorial. Erected by the village historical and archaeological society in 1997, the sign reads:

GREAT FAMINE 1845 – 1847 SITE OF SOUP HOUSE

Famine, however, is not the appropriate word to describe what happened when blight rotted potato crops in those years. Potato provided the staple food of subsistence farmers, especially the Irish-speaking folks in the then much larger Gaeltachtai in the west and south of the country.

More than a million died of starvation. A similar number sought refuge by emigrating, initiating a decline in the total population that in part accounts for the relatively low population living in Ireland today. Combined with a certain reluctance to teach Irish to children in schools that had begun in the 1930s, it was this Great Hunger that brought about the greatest decline in the use of the Irish tongue.

The role of the British government during the mass starvation is, depending on how historians perceive government motivations of that time, a very dark episode in Britain’s imperial past. It is hard to explain why it was that, throughout the years of starvation, Ireland was exporting large quantities of food crops and cattle to English ports.

If anything, the behavior initiated by absentee English landlords was even worse. Many just had starving tenants evicted en masse (an estimated 500,000 people were forced off the land), raising their hovels and seizing subsistence plots so that they could turn the land into pastures to feed the growing demand for beef and butter exported to an industrializing England. The evicted were left with nothing but despair. Many starved or died of sickness.

If the arc of history is long and tends toward justice, it may well pass retribution along the way. My walk along a lane near the lodge passes an empty shell of a stone-walled house. It has no roof, nor any woodwork filling gaps left by former windows. After the First World War, when the Irish were struggling to throw off the English yoke, Irish Republican fighters would come in the night to the homes of Anglo-Irish landlords and give them 15 minutes to leave before burning their homes down. To this day, the empty shells of former homes can be seen in the Irish countryside, especially in areas where strong republican sentiment predominated.

One notable exception to the burnings was Lismore Castle, which was never torched. Perhaps this was because during the Great Hunger the then Duke of Devonshire went to considerable expense to make sure no one went hungry at his Irish seat. Today, wealthy visitors can rent a wing of the castle and pretend to a dukedom.

While many of the larger urban concentrations on the island are in proximity to the sheltered east coast and England, the Gaeltachtai are now mostly confined to remote parts of the jagged peninsulas near the Atlantic coast. Close to one of these small Irish speaking areas in County Cork, the lodge is in an area where 45-70 percent of respondents in the 2011 census said they could speak Irish.

.jpg)

Yet, I cannot recollect ever hearing anyone speak Irish in an everyday social context except for snatches of conversation I would hear on FM radio. I admit, however, that I can barely understand some of the older folks who speak English with such a brogue that it could as well be Irish to my untrained ear.

But this was never a concern when, with dogs on the leash, I would walk out of the lodge and up lanes between dry stone walls or earthen dikes covered with grass and thorny gorse. In modern Ireland, however, one must be ready to pull dogs into the verge at a moment’s notice should a farm tractor as large as a six-wheel truck hauling an even larger trailer of winter feed for cows come around the corner.

Despite the hazards, walking in rural Ireland is one of its great pleasures, whether you are hiking on trails through moorland sodden with rain, sauntering along a sandy beach or searching out megaliths in a countryside crisscrossed by lanes in a network as complex as a piece of Irish lace.

Being unable to speak Irish was never an issue when I walked across the bridge over the river into the village to buy some milk and pick up a copy of The Cork Examiner from Ted and Maureen’s small general store. The lone village shop doubled as a post office, had a gas pump and, along with the pub across the road, was a daily point of social interaction.

On my last visit a little more than a year ago, Ted and Maureen had retired, and the shop had been replaced by a hair salon. The gas pump had gone, and I had to go to the pub to get a quart of milk.

Ireland is changing. The globalizing forces of organizations like Apple Inc., which has its EU HQ in Cork, are accelerating the secularization of Ireland’s peoples. At the same time, the grip of the Catholic Church over the population has been greatly weakened by the exposure of shocking atrocities perpetrated in the Magdalene Laundries, and the gross immorality of a church that was protecting priests who were sexually abusing minors. The changes in social attitudes helped decide the Irish to sanction same-sex marriage and abortion in referenda in 2015 and 2018. Both were issues which had once been anathema to a population deeply rooted in the Catholic faith.

Covid-19 will also shake presumptions and for a time gut tourism in Ireland, an industry that normally earns more than six percent of Ireland’s GDP. It has also been encouraging a unified approach to the pandemic between the six counties of Ulster that form Northern Ireland, which is ruled from London, and the Republic of Ireland ruled from Dublin.

Meanwhile, the British government appears to be using Covid-19 as a screen to seemingly ignore the prospect of a no-deal exit from the EU at the end of the transition period on December 31, 2020. It is the open border between Ulster and the Republic that has proven to be the thorniest issue of the Brexit negotiations.

According to the UK House of Commons 2020 briefing paper, UK exports to Ireland represented 5.5 percent of all UK exports, while UK imports from Ireland represented 3.2 percent of all UK imports in 2018. Though around 12 percent of Ireland’s physical exports and 16 percent of its services were to the UK in 2017, the trend is downwards as Ireland diversifies export destinations, especially with help from its EU partners. A part from damage to sectors like beef and dairy exports that have traditionally been heavily dependent on UK markets, a no-deal Brexit could hurt the UK proportionately more than Ireland.

The balance of trade was doubtless among factors that in early 2019 led Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar to describe Brexit as a “real act of self-harm,” but it is the proposed customs border down the Irish Sea after Brexit that would separate Ulster from the United Kingdom that, if implemented, will change everything.

For how much longer will the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland” stamped in gold on the front of my British EU passport endure? Will the majority of people in the six counties of Ulster who voted in favor of remain in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum one day opt for closer union with their southern compatriots?

If circumstances lead to a reunion between Northern Ireland and the Republic, only then will all the inhabitants of the Emerald Isle and its fair lands have broken free from the 800-year-old imperial grasp of a disunited kingdom to be.