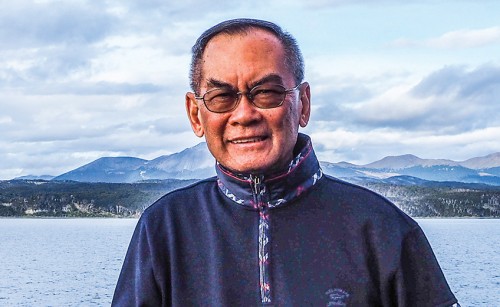

During my three-year stay in Japan, Japanese would always proudly inform me that in Japan there are four seasons, as if their country was unique in having winter, spring, summer, and autumn. Truth be told, there are more like six seasons (which is indeed unique) in the Land of the Rising Sun, as early June brought tsuyu, the onset of a summer rainy period, and then the early fall brought the typhoon season, which played havoc on a period during which other temperate climates celebrating autumn were enjoying the best of weather.

Physically and geologically, Japan has to be one of the roughest parts of the planet to inhabit. It suffers from constant earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, and volcanic eruptions, and roughly 80% of its gorgeous mountain terrain is uninhabitable, meaning you’ve got 125 million people all crammed into the sparse plains and coastal cities.

Yet the tiny island nation is one of the most beautiful places in the world, and seasons are indeed celebrated with reverence in Japan, partly because of the Shinto-originated belief of mono no aware, which roughly translates into an awareness of the impermanence and transience of all things in life. It’s a kind of bitter, sad, and at the same time appreciative state, one of total realism, and the changing seasons and their effect on the natural world embody this concept completely.

In the spring, the cherry blossoms fill the country with colour and parties are held throughout the nation celebrating their arrival. Yet, and just like that, one of the world’s most beautiful spectacles is over within less than two weeks. The blossoms are born, they amaze, and then they wither and die, and this is repeated again and yet again completely out of human control, much like our own life journeys and subsequent passing.

I was fortunate enough to spend an autumn week in Kyoto a year ago, happening to arrive right at the peak of autumn colours, and found myself walking around in constant rapture. The week passed by in a blur, but upon returning home and giving closer inspection to my photos, it was as if I had inhabited the most perfect dream, and even today, when I look back upon all my many world travels, I felt that it was this week in Japan that perhaps was the most precious of them all.

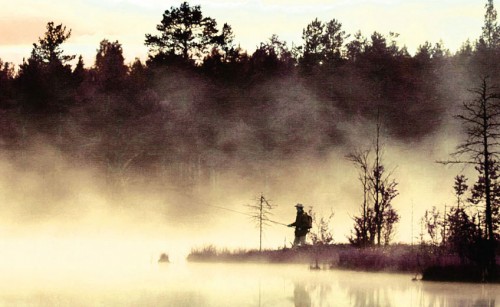

I would rise at dawn every morning, setting out, usually by bicycle, along the bike paths on the Kamo River, aiming for different temples and shrines. At the Eikan-do Zen temple, red maples and stone arch bridges were perfectly reflected in carp ponds, silent and still in the early hours of the day.

As I departed to go further afield, groups of young women clad in traditional kimonos were arriving, chatting amiably and taking selfies one minute, and yet silent and sombre the next, as they watched nature’s spectacle unfolding, perhaps contemplating a similar fate for themselves, a revolving cycle of beauty and death.

Further afield, at the Sanzen-in temple, visitors sat on the outer porch of the temple gazing at stone statues in moss-covered gardens, again silent and awe-struck. While Japan is noted for its politeness and consideration, at this time of year these traits seem to be ratcheted up even more, as even at the most crowded temples and pilgrimage sites, hundreds, and at times even thousands, of visitors watched the leaves in collective silence, occasionally bowing to their neighbour or ducking out of the way to let someone else take a photo or have a better view.

At places like the grand Kiyomizu-dera, an ornate Unesco World Heritage Site temple that was founded in 778, and perhaps Kyoto’s most famed tourist attraction, the spacious veranda was packed daily with throngs of leaf viewers, especially at the onset of evening, when lights were turned on, illuminating the vivid colours even more.

The crowds here were a bit much for me, and while Kyoto has been romanticised by poets, priests, and writers since times immortal, make no mistake about it, it is today a big modern city. Yet whenever I felt the slightest sense of being overcrowded or hemmed in, it was easy enough to escape.

The Kyoto Trail is a 70-kilometre loop trail that circles the city, travelling over mountains and along forest paths and rivers. Easily accessible by public transport, it nevertheless feels miles removed from the city’s concrete centre. One end of the route starts by the famed Fushimi Inari Shrine, where one walks up through thousands of vermilion torii gates into the forests below Mount Inari (Inari is considered to be the Shinto god of rice).

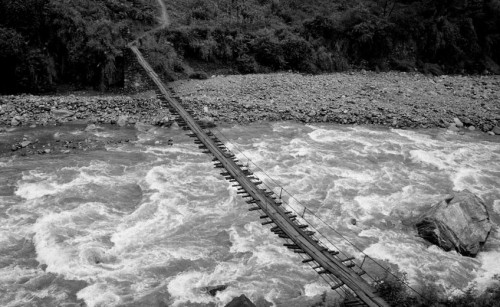

The maple trees here were not as vibrant as below, perhaps due to the vivid colours of the torii gates complementing, or overshadowing them, yet further along the trail, where it meandered along the banks of the Hozo River, the trees were dazzling, and other than a few dog walkers, I was alone.

From the river, I climbed up a ravine that is home to one of Kyoto’s best kept secrets, the hidden-away Kuya-no-taki waterfall, named after a 10th century holy man and set in a grotto filled with small shrines and Buddhist figures. I marvelled that I wasn’t more than 20 minutes away from the crowds, and yet here I had Kyoto all to myself.

The same went for lesser-known shrines along the trail as I continued along. At the Shizuhara Shrine, a majestic golden gingko tree stood in wonderful contrast to its neighbouring maple, its autumn leaves like a golden temple roof. Much harder to stumble upon than the ubiquitous maples, I had the magical tree all to myself, until a local farmer appeared, bowing at me, and then joining me in silence as we revelled in the natural beauty.

Shyly, the older man turned to me, bowed again, and asked if I could speak some Japanese. I told him that I used to live here and could understand a bit. He said, “You know, in Japan we have four seasons.” I smiled, and we both went back to looking at the leaves.

I marvelled as to how in a life and a world where nothing is ever perfect, for a few brief weeks and moments every year in Japan, everything is indeed as close to the sublime as it gets.