For years I longed to visit Tibet. Maybe it was a fascination inspired by romantic movies or the powerful lure of a distant land of myth and legend that few western travellers have seen, but I could barely contain my joy as I crowded at a portal window to steal a momentary glimpse of a magical snow-capped mountain as we made our descent into Gongkar Airport.

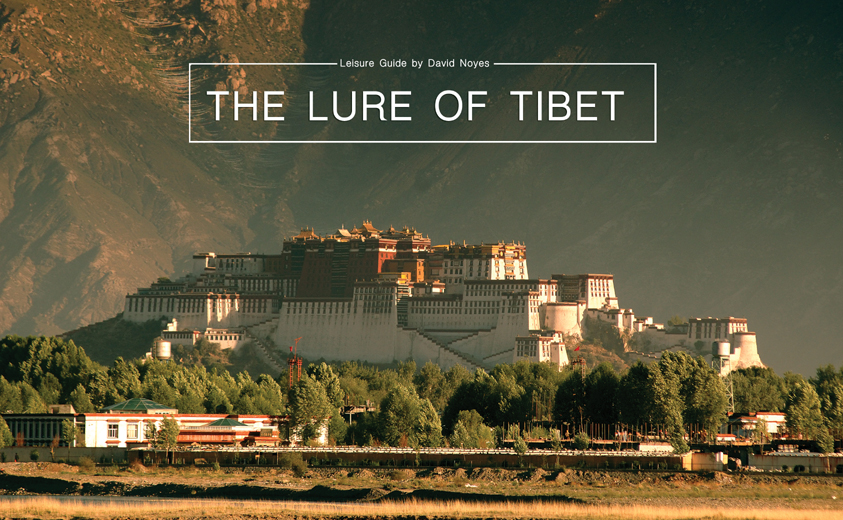

I was travelling alone on a spontaneous trip to photograph this beautiful land, but my journey to Tibet began over 20 years ago. I vividly remember being captivated by a fleeting image of the Potala Palace in a television report that described how this isolated and obscure place on the roof of the world was increasingly accessible to a tightly controlled and limited number of outsiders. My pilgrimage started that day.

Just hours after arriving in Lhasa I felt compelled to disregard the advice of my Chinese tour guide and took a taxi across town to the Potala Palace. I had come from sea level in Beijing to over 3,660 metres (12,000 feet) in a matter of hours and was advised to take my first day slowly. But I felt wonderful and wanted to experience a bit of Tibet before I settled into my comfortable room for the night and the controlled itinerary of my guided tour.

The drive down Beijing Road revealed what a large and increasingly modern city Lhasa had become. I was a bit surprised – and a bit disappointed – that the once-forbidden city was now a sprawling mini-metropolis of 200,000 people with contemporary buildings, shopping malls and nightclubs. I couldn’t help but think that maybe I was too late to experience the Tibet of my romantic vision. That feeling quickly changed to a childlike exhilaration when the Potala came into view through the dusty windows of my Lhasa taxi.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at the Potala, but there were still dozens of pilgrims wandering the streets and prostrating themselves on the sidewalk in front of the towering palace perched high on the terraced slope of the 130-metre “Red Hill”. I took several photographs of beautiful women who appeared not to be bothered by my camera or my presence as they practised their faith. The sounds of chanting and the clanking of hand-held prayer wheels would soon become familiar background music, but for now they were an unfamiliar and authentically Tibetan experience that would permeate my dreams for several nights. After a few minutes to absorb the realization that I was actually standing in front of the Potala, I had no trouble waving down a taxi and headed back to the Tibet Hotel.

After a restless night, the tour group I was joining began a series of short excursions to monasteries and sites on the outskirts of Lhasa. On consecutive days, we visited the great Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) monasteries of Sera and Drepung. From the 17th century until recently, Drepung was the largest monastic university in the world and home to as many as 10,000 monks.

My visit to Drepung reflected a much different time in the history of this once-magnificent monastery tucked at the base of a hillside just 8km west of Lhasa. Drepung sustained very little damage during the Cultural Revolution, and its complex cluster of white buildings with narrow cobblestone roads resembles a small Mediterranean city. I was surprised at how few people we actually encountered. There were very few pilgrims, no other tourists, and although we were told there are 700 monks currently in residence, the only monks we met were found sitting in dimly lit corners of the various chapels, diligently thumbing through scriptures while collecting the small 20 yuan fee we were each charged to take pictures.

I shuffled quietly into a small room illuminated by the golden glow of yak-butter candles when my eyes unexpectedly made contact with an elderly monk. He smiled at me and asked, in perfect English, “Where have you come from?”

“The United States,” I answered.He took my hand as we walked clockwise past a Buddhist shrine and whispered in a voice so quiet I could barely hear, “You have journeyed a very long way to visit Tibet.” I was overwhelmed by the warm touch of this graceful man. Before releasing my hand, he looked at me with his gentle smile and instructed, “When you return home … remember to pray for Tibet.” It was just my second full day in Lhasa, but at that moment I knew my experience would be unforgettable.

According to legend, Buddhism was received into Tibet’s shamanistic warring culture when 400 Buddhist scriptures fell from the sky onto the roof of the Yumbulagang fortress in the fifth century. Most modern scholars, however, believe that Buddhism was established in Tibet during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo, who died in 650 CE. Under the rule of Songtsen Gampo, Tibetan influence continued to expand through force of arms into inner Asia, northern India and Nepal. It was also during the time of Songtsen Gampo that Jokhang temple was built in Lhasa.

Although very little remains of the original seventhcentury structure, the Jokhang is the holiest of all holy places in Tibet and its layout is ancient. As I listened intently to our guide describe the confusing and unfamiliar icons in the numerous small chapels, I would occasionally feel a little nudge in the small of my back only to turn and see a tiny Tibetan woman eagerly attempting to pass. Chapel after chapel, devout pilgrims gently made their way past scores of tourists to touch their heads and pay tribute at the altars of gurus, buddhas and kings. After spending some time admiring the jewelled statue of Songtsen Gampo, who was flanked by his two wives, I quickly moved through the other chapels of the inner sanctum and followed our guide to the roof before making my way back down to the ground floor and out to the Barkhor.

As I began to explore the Barkhor, Tibet’s famous pilgrimage circuit (kora), I stopped at the main entrance of the Jokhang. As dusk began to settle over Lhasa, I sat reposed for over an hour on the stone steps that lead down to a forecourt and watched as worshipers who had travelled for weeks and months to Tibet’s most sacred temple raised their hands in a simple gesture, gently touching their forehead, mouth and chest before lying prostrate, face down on the stony ground, their hands protected by gloves of wood. The air was fragrant with the smell of incense and human sweat, providing an additional olfactory authenticity to my experience.

I found it hard to leave the forecourt, but the day was nearing an end so I reluctantly began my swift walk on the Barkhor. In fact, I was literally swept along the circumambulation route by the force of both pilgrims and tourists. The narrow streets were lined with stalls and shops selling butter oil, wicks, khata (a silk offering scarf signifying purity and goodwill) and incense for worshipers, as well as cheap jewellery, prayer flags and assorted trinkets that I scarcely stopped to notice. Unlike the rhythmic chanting of “om mani padme hum” that lifted skyward on the soft breeze in front of the Jokhang, the Barkhor was alive with the sounds of chatter and commerce.

After several days exploring monasteries, temples and shopping areas, we packed our belongings and boarded a comfortable motorcoach for a multi-day excursion into the Yarlung Tsangpo Valley. The Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra River) is referred to as the “mother river of Tibet”. Originating at over 5,000 metres, high in the glaciers of the Himalayas, the Yarlung Tsangpo drains an area of 240,000 square kilometres) with an average elevation of around 4,500 metres, making it the highest river in the world.

Just a short distance outside of Lhasa, we made our first stop, at the Gongkar Chöde Monastery. As we entered the dark inner sanctum of the main assembly hall, we were greeted by the familiar smell of yak butter candles and the melodic sound of monks at prayer. Several generations of monks sat cross-legged on padded benches draped in their burgundy and saffron robes, appearing only mildly distracted by the flashes of a dozen camera-clicking onlookers. The sight of tourists moving freely taking pictures among rows of meditating monks seemed a bit insensitive, but the opportunity to experience and photograph this solemn scene was irresistible. After nearly a dozen tours of temples and monasteries, I was thrilled to see and hear a room full of monks in an authentic demonstration of piety and devotion.

We spent the night in Zetang Township at a nice hotel in the centre of a very poor village on our way to Bayi. From here it was just a short 12km drive the following morning to our next stop at the spectacular Yumbulagang Palace. Yumbulagang rises from the summit of Mt Tashitseri on the eastern bank of the Yarlung Tsangpo like a medieval European castle. We made several stops along the highway to photograph the towering structure that dominates the Yarlung skyline before our bus stopped at the base of a steep mountain approach.

From the parking area, we were offered an option to walk up the steep switchbacks or ride to the palace on a mule for the affordable fee of 10 yuan. There was a small line and a bit of commotion as another group of tourists started up, but without hesitation I mounted my mule and trotted up the mountainside led by a young Tibetan. He held the mule by a short rein and enjoyed having my faithful ride break into a canter on the sharpest hairpin turns. It was a dusty, hot beginning, but once on the top of the hill, it didn’t take long to explore the two interior chapels of Yumbulagang.

Inevitably, we began the long journey back to Lhasa through the Mi-La Mountain Pass, and I started to accept that my Tibetan experience would soon end. The distant sounds of monks chanting, the pervasive odour of yak butter candles, and the warmth I felt in my soul from the kind toothless smile of a pilgrim, would soon become personal memories from the high plateau that would only survive in morning ready to tour the Potala Palace on my last day in Tibet. I was glad that my visit would end at the place that inspired my journey so long ago. But as expected, the 350-year-old former seat of the Tibetan government and winter palace of the Dalai Lamas is an eerily quiet museum with gift shops offering books and trinkets celebrating the long history of this magnificent building. Scores of tourists and pilgrims lined the dimly lit hallways leading to small rooms and chapels that were once alive with activity.

It felt both awkward and disrespectful to be standing in the doorway, voyeuristically peeking into the private bedroom of the 14th Dalai Lama, presented as if he would be returning at any moment. For the first time in my visit I no longer viewed my experience as a detached traveller drawn by a mystical lure to an enchanting destination. I began to wonder what might have become of Tibet if history had taken a different, less violent, path.

I came to Tibet to see for myself if the magical place of my imagination – filled with ancient rituals, cloistered communities and an indigenous culture that celebrated a profound spirituality – still existed on the roof of the world. The reality of modern Tibet is obviously very different from my romanticized vision. However, with the promise of increasing autonomy, prayer wheels are again spinning and prayer flags once again release “om mani padme hum” to the heavens while monks equipped with cell phones lead the great monastic institutions towards a new partnership with modernity.