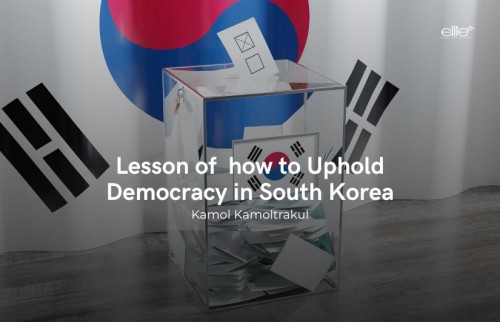

The Diplomat online magazine once called Korea, during its military dictatorship, the “Republic of Total Corruption” because corruption during that period was systemic as leaders used their power to enrich themselves and their allies. These men emphasised loyalty of the corporate oligarchies, which are now behind the recent corruption scandals. Justin Fendos, a professor at Dongseo University in South Korea, says it has been the norm that executives in both corporations and government hire relatives, close friends, acquaintances and classmates to fill the managerial positions below them. Koreans call these relationships “ropes”, the equivalent of American coattails. Meanwhile, their government cronies use kickbacks to finance election campaigns, that is buy off supporters, to be re-elected and enrich themselves.

In fact, political corruption in South Korea has been a significant issue throughout its modern history, often intertwined with the country's rapid economic development, authoritarian past, and democratic transition.

During military rule, the Government maintained close ties with “chaebols” (large family conglomerates), exchanging political support for economic favours, monopoly rights, export rights and government loans, making scandals plentiful. The biggest case that shocked not only Koreans, but also the world, was the Daewoo corruption scandal.

According to BBC News, South Korean prosecutors filed charges against over 40 top executives, in has been described as the Daewoo corruption scandal. This was related to the discovery that company's auditors concealed the company’s amount of debt, and that bribes of about 470 billion won (close to USD 400 million) were involved. Loss from bribery and corruption has been estimated at over USD 1 billion.

A deception worth 22.9 trillion won (USD 15.3 billion) that was called the "biggest accounting fraud in history”, surpassed the WorldCom and Enron cases.

Daewoo was a sprawling enterprise with over 320,000 employees and 590 subsidiaries overseas that operated in over 110 countries. Its management received widespread praise and academic recognition for its success.

Scandals have also been associated with Korean Airlines, Hyundai, Samsung, Hanjin and Lotte. Under leaders like Park Chung-hee (1961–1979) and Chun Doo-hwan (1980–1988), South Korea's political system was highly centralized and authoritarian. Bribery, embezzlement and cronyism were widespread while dissent was suppressed, limiting accountability.

The Korea Times reported past Key Political Corruption Scandals include:

1. Roh Tae-woo Slush Fund Scandal (1995)

Former President Roh Tae-woo was found to have amassed a slush fund of over USD 650 million during his presidency, much of it from chaebols in exchange for favours. He was convicted and sentenced to prison, marking a significant moment in South Korea's fight against political corruption.

2. Kim Young-sam's Son's Bribery Scandal (1997)

President Kim Young-sam's son, Kim Hyun-chul, was arrested for accepting bribes from businesses in exchange for influence. This scandal tarnished Kim's legacy as a reformist president.

3. Lee Myung-bak's Corruption Case (2018)

Former President Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) was convicted of embezzlement, bribery, and abuse of power, involving tens of millions of dollars. He was sentenced to 17 years in prison, though his term was later reduced.

4. Park Geun-hye and Choi Soon-sil Scandal (2016–2017)

President Park Geun-hye (2013–2017) was impeached and removed from office following a massive corruption scandal involving her confidante, Choi Soon-sil. Choi was found to have used her relationship with Park to extort millions of dollars from chaebols and influence government decisions. Park was sentenced to 24 years in prison (later reduced to 20 years) before being pardoned in 2021.Prosecutors allege that Lee donated 41 billion won (USD 36m) to non-profit organisations linked to Park’s close friend and advisor, Choi Soon-sil, to secure government support for a merger that would help him to the top of the Samsung group.

Analysts point out that corruption has a significant negative effect on economic growth through its impact on investment, competition, entrepreneurship, government efficiency and human capital formation. It also has important implications for numerous indicators of economic development such as environmental quality, personal health and safety, income distribution and social trust. Thus, reducing corruption has become a top priority.

Hence, with strong pressure from the democratic movement, since the Kwangju Uprising, involving students, academics and NGOs, toppled military rule in 1980, in January 2021, the South Korean government formally established the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials (CIO) to investigate corruption involving current and former senior officials, including lawmakers, prosecutors, judges, presidents, prime ministers and officials’ family members; in the case of presidents, the definition of family members extends to cousins.

The CIO is authorised to investigate certain crimes, including bribery, embezzlement and breach of trust, abuse of authority and perjury. The CIO is also authorized to investigate all individuals implicated in the crimes under investigation, even if they are not themselves high-ranking officials. Other law enforcement agencies that become aware of any crimes that fall under the jurisdiction of the CIO must immediately notify the CIO, and the CIO can compel the relevant agency to transfer the case to it.

The role of regulators with jurisdiction to prosecute corruption are the key to fight corruption. The Prosecutors’ Office and the police are two agencies that also prosecute corruption. They have special investigative departments that perform criminal investigations on corruption.

Anther anti-corruption mechanism set up, the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC), has as its role to receives information or complaints filed by whistle-blowers and members of the public. For the financial sector, the Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) and Financial Services Commission (FSC) conduct investigations as administrative agencies, and depending on their findings, may render administrative sanctions on a corporate entity. For rebates in the medical sector, the Korean Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) conducts investigations and may render administrative sanctions on a corporate entity. These agencies may also hand over their findings to the Prosecutors’ Office for criminal prosecution in cases involving bribery and other applicable corruption-related crimes.

&One catalyst for Korea’s improved performance has been the Anti-Corruption and Bribery Prohibition Act that took effect in 2016. It sets rules on gifts of money, goods and services to public officials (including those at state-owned enterprises and government institutions), private school employees and journalists. Gift-giving is an important aspect of Korean culture to show respect and gratitude and build relationships, including in the workplace.

The law initially covered over 40,000 organizations and about 9% of the Korean workforce. Those subject to the law could not receive meals worth more than KRW 30,000 (USD 26 at the 2016 exchange rate), gifts over KRW 50,000, and cash gifts above KRW 100,000 at private events, including wedding ceremonies and funerals . The Constitutional Court upheld the law despite complaints that it would hurt certain economic sectors.

In conclusion, South Korea's fight against corruption involves a combination of strong legal frameworks, technological innovation, public engagement and international cooperation. While challenges persist, the country's proactive approach serves as a model for other nations seeking to combat corruption effectively.

South Korea has established stringent anti-corruption laws such as the “Kim Young-ran Act (officially known as the “Improper Solicitation and Graft Act”), which came into effect in 2016. This law prohibits public officials, educators and journalists from receiving gifts, meals, or money exceeding certain limits, regardless of whether it is related to their duties.

Then there is the independent Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission (ACRC), the primary agency responsible for investigating corruption, protecting whistle-blowers and promoting transparency. Third is the whistle-blower protection laws that encourage individuals to report corruption without fear of retaliation, and finally, South Korea has invested in anti-corruption education and campaigns to raise public awareness about the negative impacts of corruption.

According to a Transparency International report, South Korea has implemented a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach to combat corruption that has evolved significantly over the years. The perception of corruption in Korea has diminished considerably during the past decade. In the Corruption Perception Index, Korea rose from 31st among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries in 2016 to 22nd in 2023 while the rankings for the United States and Japan declined or remained stable. The World Bank’s Control of Corruption measure also shows a similar trend. By 2022, Korea’s ranking was close to that of the United States. Korea scored 63 Points in the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) while Thailand had a score of 35 points placing it 108th out of 180 countries, compare to a score of 36 out of 100 in 2022, or one point lower.

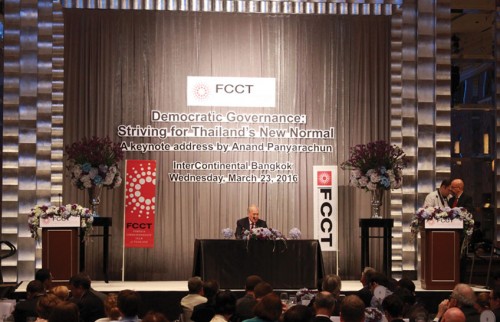

The lessons from South Korea's anti-corruption efforts, which involve strict and non-discriminatory enforcement of laws, are noteworthy. South Korea has a transparent, robust, and independent justice system. Its judiciary operates with fairness and independence, remaining impartial and free from bias, adhering to universal principles of the rule of law. Therefore, it is worth studying and applying these practices to reduce corruption in Thailand effectively.