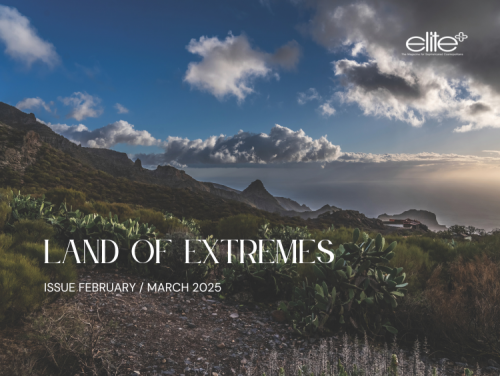

It was the heaviest blizzard in two generations. The Hellenic capital, better know for its stifling summers, was snowed in. Snowfall reached as far away as the party island of Mykonos. Cars headed north could no longer navigate the snow drifts and were abandoned on the highway. And with energy prices sky high and the nation still burdened under austerity and debt from the brutal Greek financial crisis of 2007-2008, most buildings could not afford to turn on the central heating, making the icy temperatures all the more piercing and unreal. Added to this was a second year of restrictions due to Covid, which hit the ageing country hard and prevented more than a trickle of visitors from arriving. And on top of that has been a surge of refugees from Syria, northern Africa and elsewhere over recent years, swamping public services and making it harder to climb out of debt. Yet the national spirit is unbowed, the people as kind and generous as ever. In the weekend flea markets of Monastiraki, in the cafes Kypseli or Kalithea, in the gentrified suburbs or the impoverished centre, there is a palpable pride in achievements of the past, when Hellenic science was the world’s most advanced, when its language infused most of the languages of Europe, when philosophers introduced the concept of democracy; or when Alexander conquered the known world or Byzantium ruled the eastern Mediterranean. In a globalised world, Greece remains unique. With its own script, its own approach to quality of life, the elements that make it one of a kind become more apparent in the absence of tourists. In an unexpected wintry wonderland, everywhere one looked pulsed the ancient heart of Athens.

Athenian winter : Greece is known for Mediterranean sun and sea holidays, but a trip to a capital under lockdown and snowfall is a rare and fascinating experience