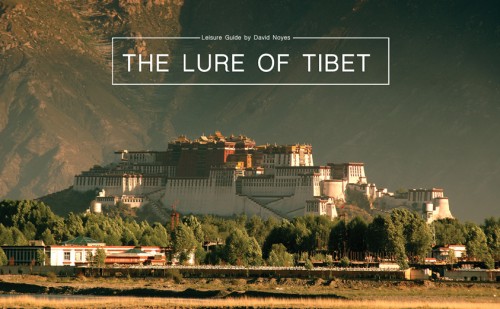

Comfortable beds, good food, a relaxing holiday? If those are important, you probably shouldn’t read on. The Pamirs of Tajikistan offer none of the above. But if you are a trekker, cyclist or intrepid traveller looking to do perhaps the world’s last great road trip, crossing the Pamir Highway should be at the forefront of your bucket list.

.jpg)

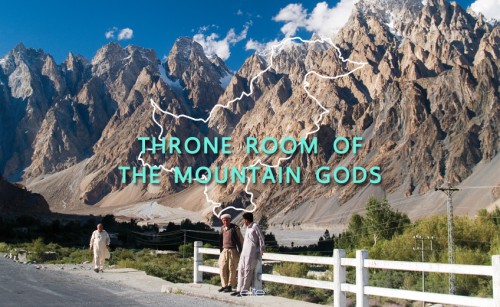

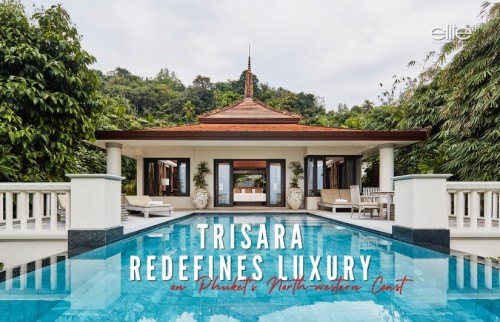

The Pamir “Highway” (forget about pavement, this is a potholed, stone-filled and sandy track that traverses some of the most spectacular high desert and huge mountain landscapes on the planet) runs from western Kyrgyzstan across the slightly misnamed Pamir Mountains (a “pamir” is a high mountain pasture, whereas the road crosses dozens of different mountain ranges that include the Great and Little Pamir of Afghanistan) from Osh in Kyrgyzstan to Dushanbe, the Tajik capital. Crossing passes of over 4,600 metres, it’s the second highest road in the world, stretching some 1200 kilometres through a sea of spectacular desert and mountain landscapes; harsh, extreme (from baking hot summers to minus 40 degree winters), remote and wild, pretty much everything a lover of emptiness, solitude and getting off the beaten path could dream of.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

My partner and I, along with two good friends, spent the better part of a month travelling this wild landscape; journeying by Land Cruiser, yak, donkey and on foot for much of the time. Our route initially followed the barren Murghab Plateau, where the elevation never drops below 3,500 metres, and where Marco Polo sheep and snow leopards still roam across rainbow-coloured desert ranges interspersed with hidden hot springs, geysers and mineral deposits. Much of the population here are Kyrgyz nomads, who move their animals up to high pastures to graze, setting up yurt camps where we were warmly invited in for cups of butter tea and fresh dairy products like yoghurt kefir and sour cheese.

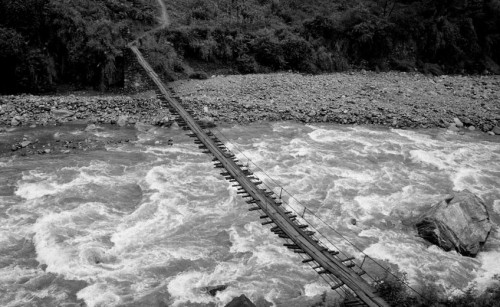

From here, we dropped into the Wakhan Valley, where the route follows a tortuous path alongside the raging Pamir River, which turns into the Panj, an 1,125km swath of glacial meltwater that separates Tajikistan from Afghanistan, close enough on the other side to wave at villagers working in their riverside wheat fields. In the Wakhan, Asian features disappear and are replaced by surprisingly piercing green and blue eyes, freckles and other European features (it is claimed Alexander the Great and his men spread their genes when they travelled through during his military campaigns across Central Asia).

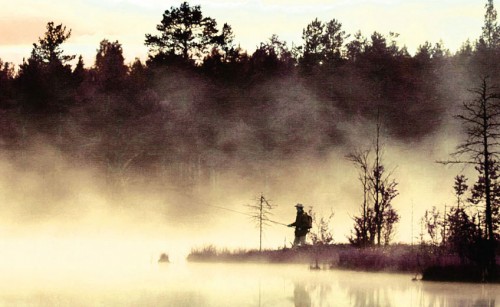

In the Wakhan, the immense peaks of the Hindu Kush, Great and Little Pamirs, and Wakhan Range rise dramatically above the valley floor. Like elsewhere in the Pamirs, emerald Alpine lakes appear from nowhere, almost like mirages surrounded by the arid desert conditions, and we spent several days trekking above pristine Lake Zorkul, half of which belongs to Afghanistan and half Tajikistan, seeing no humans for three days, and finding one of the most blissful and picturesque camp spots I’ve ever had in my many years of wandering the globe.

Conditions along the Pamir Highway are a mix of spellbinding beauty and harsh desolation. There are few hotels outside of Khorog, although locals in villages open their homes to travellers and offer basic floor space, fresh nan bread and traditional Pamiri hospitality, which makes up for the lack of showers, primitive outhouses and other amenities. The climate adds to the challenges, as even at altitude, summers are brutally hot and dry, especially testing the limits of those travelling by bicycle, motorcycle or on foot. Nights can be bitterly cold, passes can be blocked by snow at any time of year and dust is guaranteed to be a constant companion. Yet it is all worthwhile. I often looked around in amazement, whether at the glistening white peaks towering over the otherwise sun-baked brown surroundings, or at the turquoise salt lakes like Karakul, a massive 25km lake set in an impact crater at just shy of 4,000 metres, higher than South America’s fabled Lake Titicaca.

Tourism is trickling in to the Pamirs. We saw bands of motorcyclists, loads of touring bicyclists and even the odd tricked-out vehicle from Europe, outfitted with every possible gadget needed to cross the Roof of the World inching their way across the vast open spaces. But for the most part, we had endless moments of solitude and a tremendous feeling of being small, just grains of dust set in a living geological wonder. For the adventure traveller, this is about as close to nirvana as it gets.

.jpg)