Lesson of how to Uphold Democracy in South Korea

Democracy in South Korea has been tested. However, South Korea has shown to the world that its democratic system is effective. It was proven by the Constitutional Court‘s recent unanimous decision, 8-0, on Friday, 4 Apr 4 2025, which ruled that impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol had committed "grave violations" by imposing martial law on 3 Dec, following his impeachmen.t The ruling stated that Yoon's abuse of power in declaring martial law and other actions “constituted serious violations of the principles of democratic governance and the rule of law”, Yoon will now face more intense criminal investigations.

The impeachment of Yoon Suk-Yeol sparked a new and broader discussion among scholars about the resilience and maturity of South Korea’s democratic system.

A political analyst from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said that after months of political turmoil and intensified bitter divisions, the court’s final verdict helped heal wounds and bring the nation together. That the court produced a unanimous decision to uphold Yoon’s impeachment was no surprise. It has done so in all three presidential impeachment cases, to minimise potential conflict between different political groups and their supporters.

Beyond its power to protect and uphold the constitution, the Court also serves a key political and social function: To bring a politically divided nation together through fair and just legal proceedings and decisions.

According to Darynaufal Mulyaman, the director of the Center for Securities and Foreign Affairs Studies (CESFAS) at the Universitas Kristen Indonesia, this rapid response emerged from democratic practices embedded in South Korean society that were forged through decades of resistance to authoritarian rule and modern education, social networks and technology.

South Korea, with a population of 51 million, boasts near-universal digital connectivity. Over 90 percent of South Koreans use social networking platforms such as the homegrown KakaoTalk, which alone serves nearly 49 million users in South Korea—bridging a society where many still recall first-hand the struggle for and transition to democracy. The democracy movement isn’t just history, but is also actively taught in schools as part of national identity. Although many scholars have dissected South Korea’s ethnic homogeneity, a strong sense of civic duty forms just as much of the glue tying together South Korea’s imagined community.

Moreover, another organisations at the forefront is the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), one of Asia’s most powerful labour organisations that represents 1.2 million workers across South Korea’s key industries, instead of fragmented labour movements. Umbrella organizations such as the KCTU create cross-sector incentives for coordinated action, amplifying organized labour’s leverage. Within hours of Yoon’s announcement, the KCTU called for a general strike—a move that, pending member unions’ decisions, will threaten production at many of the nation’s most vital industries as well as critical public services such as healthcare and transportation.

The KCTU’s mobilisation carries particular weight with the pro-business Yoon administration, given South Korea’s position as the world’s twelfth-largest economy and a crucial link in global supply chains, especially for semiconductors and electronics. The KCTU’s strike threat will put tangible economic pressure on the country’s leadership and combined nationwide mobilisation by citizens and student groups. It demonstrates how deeply democratic values have become embedded in South Korean political culture.

In addition, lessons from the bitter history of fighting against the military dictatorship in the 1980s are remembered by the powerful coalition of labour unions, farmers, students and middle-class intellectuals who pushed back against brutal military rule. They built what scholars call networks of contention—social and organizational connections that facilitate collective action and resistance through sharing resources, information, organizational capacity and trust, even in high-risk contexts. The civic legacies of the twentieth century remain vibrant today in South Korea, one of the world’s most networked societies, allowing for rapid mobilisation. Now, we see the South Korean civil society networks and progressive establishment, tested through decades of resistance to authoritarianism, are mounting a coordinated response.

Furthermore, South Korea’s mobilisation networks have not only empowered grassroots activism, but also deeply influenced the growth of the progressive Democratic Party (DP) of Korea. The DP’s close ties to organisations such as labour unions, student groups, human rights advocates and professional associations have empowered it to mobilise both electoral and event-based support during critical junctures over the past thirty-plus years. Many prominent progressive leaders in contemporary South Korea—including former presidents Kim Dae-jung, Roh Moo-hyun and Moon Jae-in—played vital roles in mobilisation in the 1980s.

Hence, these legacies are often framed as imbuing the contemporary DP with moral authority to root out corruption and government overreach. It provided a powerful rhetorical strategy that resonates with many South Koreans’ direct experience. Seoul’s national track record on civil liberties, particularly when it comes to minority rights, is anaemic compared to similar post-industrial societies. The DP is no stranger to scandals of its own. In fact, it is the assumed frontrunner for a future presidential election.

However, according to Ryu Yongwook, an assistant professor at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS, there are at least three lessons to be learned:

First, a lesson for all: The rule of law means that no one, including the president, is above the law. The matter of presidential impeachment essentially turns the court ruling into a political judgment. Hence, it will please some and upset others, but everyone must accept the court’s decision if they understand that the rule of law serves the interests of all in the long term.

Second, a lesson to political parties: They must learn to compromise through dialogue. The court said that it was difficult to view the conflict that arose between Yoon and the opposition-led legislature as “being the responsibility of one party”.

The court chastised the National Assembly, saying it “should have respected minority opinions and endeavoured to reach a conclusion through dialogue and compromise” and that Yoon “should also have respected the National Assembly as a partner of cooperation.” However, it all depends on key actors drawing the right lessons, rather than utilising the court’s decision to serve their political interests.

And third, a lesson about institutional reform and legitimacy after impeachment proceedings revealed fundamental weaknesses in the current political and legal system. It must be remembered that impeached officials cease their functions immediately until the constitutional court decides on the case. A simple majority is all that is required to impeach government officials (or two-thirds for impeaching the president). This means any party with a simple majority in the National Assembly can effectively halt the operation of the government. Another is that the constitutional court itself had adopted dubious procedural rules in the impeachment proceedings and seemed to adopt ad hoc rules without firm legal basis.

In fact, this political crisis has evoked many comparisons to the 2016 nationwide protests against former president Park Geun-hye’s abuse of power. In both cases, citizens rapidly mobilised against presidential overreach, though the circumstances differ markedly. While Park’s downfall came after months of peaceful candlelight demonstrations that drew millions into the streets over her corruption scandal, Yoon’s attempted power grab was thwarted within hours through a combination of legislative action and immediate civil society response. The speed of this latest democratic defence suggests that lessons learned during decades of mobilisation have strengthened South Korea’s institutional guardrails and nationwide vigilance against executive abuse. Some scholars have compared what happened in South Korea to Thailand and feel the result here would still not be as positive under current conditions.

Eight members of the South Korea Constitutional Court

Photo by https://www.khan.co.kr

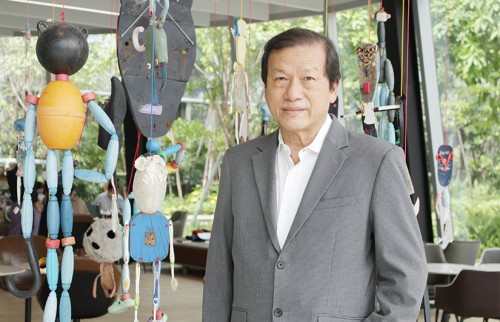

Kamol Kamoltrakul 17 Posts

Visiting lecturer: Navy Academy Institution, NIDA, School of Governor, Ministry of Interior, Chulalongkorn University, Former Lecturer, ABAC Honorary Advisor Trade and Industry Committee Senate. Senior advisor, Standing Committee on Finance and Banking, The House of Representative. Former Advisor to the Minister of Interior Board Member of ThaiPBS Board Member Of Thai Consumer Council Columnist : Prachachart Business Weekly, Matichon Weekly, Khom Chad Luke Daily Former Program Director Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development ( FORUM-ASIA).