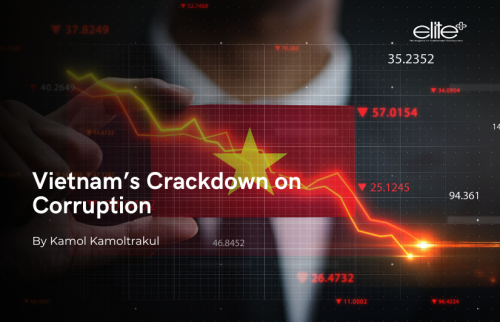

by Kamol Kamoltrakul

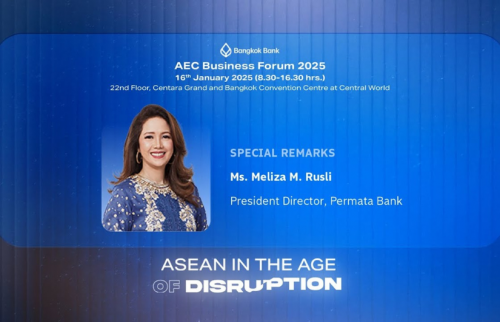

ASEAN is well prepared for the new, changing, global economic order after Trump takes office on 20 January 2025. President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign promised a more aggressive stance on tariffs than his first term, with proposals for a universal baseline tariff of up to 20 per cent on most imports and potential tariffs as high as 60 per cent on Chinese-made goods and 25-100 percent tariffs on Mexican imports.

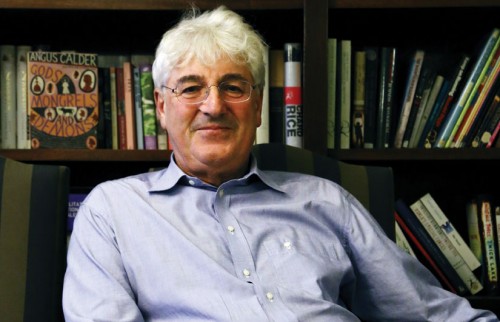

William Pesek of the Asia Times, interviewed several experts, including Dr Denis Hew, a Senior Fellow and Regional Economic Studies Coordinator at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Singapore. He said the potential economic impact of a second Trump presidency is a significant concern. Dr Hew anticipated a more intense US-China trade war with far-reaching effects on Southeast Asia.

“Southeast Asian countries are not immune to rising trade tensions that will be imposed on China and the rest of the world,” he said. “Increases in tariffs are going to disrupt supply chains again, impacting many countries in Southeast Asia, particularly in semiconductors and consumer electronics.”

Beyond immediate trade tensions, Dr Hew expressed worries about “geo-economic fragmentation” — a reversal of globalisation that could lead to segmented labour markets, reduced productivity and inflation. “We’re seeing overall greater trade fragmentation that might happen around the world. And that’s something to be worried about,” he said.

Nevertheless, according to the tax expert, this trade war would back fire, leaving no winner. The Tax Foundation, a non-profit organization, stated that over the long run, tariffs shrink the size of an economy by reducing work and investment. That’s because tariffs increase the relative prices of imported and protected goods, and after paying those higher prices, people have less income left to spend elsewhere. This means tariffs reduce the after-tax value of income by reducing how much consumption people can afford. The reduction in the after-tax value of income reduces incentives to work, which reduces hours worked and, in turn, capital investment. Fewer hours worked and a smaller capital stock result in a permanently lower level of output and income.

Additionally, tariffs lead to dynamic inefficiencies, which reduce productivity. By creating a protected domestic market, tariffs blunt competitive pressures that otherwise force firms to remain innovative. Instead of needing to constantly search for ways to improve processes and meet consumer demands, firms can sit back and enjoy higher profits from protection. Past (and ongoing) episodes of protection, both anecdotally and empirically, reveal that protected firms tend to use their higher profits to lobby for more and longer protection, rather than for increased research and development or capital expenditure.

Tariffs may also lead to inefficiencies through political favouritism and uncertainty. A new analysis of Trump’s first term tariffs found firms that made political donations to Republican candidates were more likely to be granted tariff exemptions than firms that gave to Democrats. Increased uncertainty over trade and tariff policy itself can chill investment and decrease incomes.

In an article published on 16 December 2024, the South China Morning Post also reported concerns on applying tariffs as a trade barrier. It stated that the Trump administration’s aggressive stance towards China during his first term, marked by the trade war which began in 2018, fundamentally altered the economic relationship between the world’s two largest economies.

Trump’s approach to import tariffs aligns with his “America First” economic vision, emphasising the protection of US industries to address trade imbalances. His first-term policies targeted what he described as unfair trade practices, intellectual property theft and the erosion of US manufacturing jobs, particularly in relation to China.

When Trump became president in 2017, the federal government collected USD34.6 billion in customs, duties and fees. This doubled under his watch to USD70.8 billion in 2019. US tariffs on Chinese goods also escalated to cover about USD370 billion worth of imports.

These measures had significant collateral effects on Asian economies integrated into Chinese supply chains. GDP growth in developing Asia fell from 5.9 per cent in 2017 to 5.2 per cent in 2019, partly attributable to rising trade tensions. These signals alone have prompted Asian countries to re-evaluate their supply chains and investment strategies before he takes charge.

Adapting to a Changing Global Economic Order

The implications of a second Trump presidency reflect deeper changes in the global economic order. Trump’s protectionist policies suggest long-term transformations rather than temporary disruptions.

However, Southeast Asia approaches this with strengthened resilience and strategic adaptability. “The region is more resilient — not just living through the trade war, but living through the pandemic,” Dr Hew said. Countries are diversifying economic partnerships, strengthening regional frameworks, like RCEP, and deepening intra-regional integration.

For ASEAN, Dr Hew sees potential in leveraging the bloc’s collective economic power. “We do have that economic clout, and that economy could get even bigger and stronger if we all work together,” he said, suggesting regional integration could provide crucial leverage against global uncertainties. But despite concerns about potential disruptions, he maintains a cautiously optimistic outlook. “It all depends on how the global economy is going to turn out over the next couple of years,” he said. “I’m still more positive.”

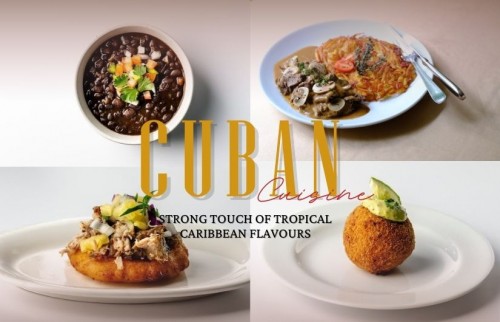

For Thailand, to leverage the impact of a trade war initiated by Trump, on Tuesday, 24 December 2024, Thai media reported that Thailand’s cabinet approved the decision to join BRICS, after the application to join had been accepted at the 2024 BRICS Summit along with Belarus, Bolivia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Cuba, Malaysia, Uganda and Uzbekistan in Kazakhstan. Speaking to the press, spokesman Nikondet Phalangkun said that Thai Foreign Minister Maris Sangiampongsa had sent a letter to his Russian counterpart confirming the kingdom’s approval to become a BRICS partner country.