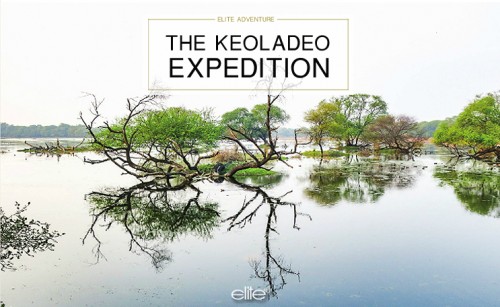

After Twyfelfontein was inscribed by UNESCO as Namibia’s first World Heritage Site in 2007, six years later, in 2013, the Namib Sand Sea was named its second, saying, “The Namib Sand Sea is a unique coastal fog desert encompassing a diverse array of large, shifting dunes. It is an outstanding example of the scenic, geomorphological, ecological and evolutionary consequences of wind-driven processes interacting with geology and biology. The sand sea includes most known types of dunes together with associated landforms such as inselbergs, pediplains and playas, formed through aeolian deposition processes. It is a place of outstanding natural beauty where atmospheric conditions provide exceptional visibility of landscape features by day and the dazzling southern hemisphere sky at night.”

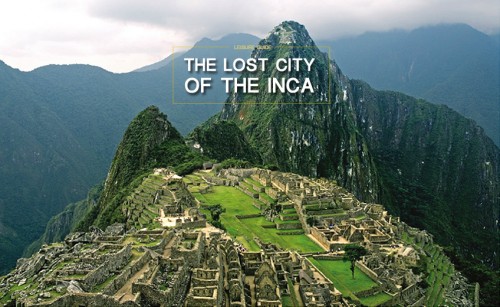

The Namib Sand Sea is located within the Namib-naukluft Park along the South Atlantic Ocean coast. It has an enormous core area of 30,777 square kilometres and a buffer zone of 89,950 square kilometres. The most well-known and visited area of the World Heritage Site is Sossusvlei, where the extensive dune fields are located, lying 363 kilometres away from Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, taking almost four hours to drive there. One of the most photographed spots in Sossuvlei is a dead camel-thorn tree standing in a dried pan with Big Daddy sand dune in the background. UNESCO has imposed ten criteria on the selection of a nominated site to become either a cultural or natural World Heritage Site. The first six are concerned with the cultural aspect of the property, while the remaining four emphasize the natural elements. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee has inscribed the Namib Sand Sea based on all four natural criteria.

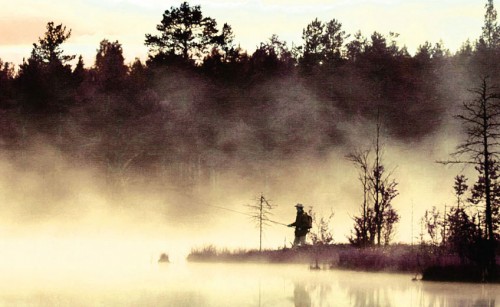

The seventh criterion states that the nominated site must contain superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance. My photos of the magnificent and diversified eye-catching dune formations with their range of changing colours truly bear witness to the natural beauty of the site. I followed the advice of my local guide to personally trek all the way up to the top of Big Daddy, the highest sand dune in Sossusvlei, with a height of 325 metres, at ten in the morning. The sunshine was most radiant at that time and turned the sand’s pale colour, which contains a large amount of iron oxide, into a deep bright red. From the top of Big Daddy, I looked across the vast dried pan at another high sand dune called Big Mama, which also appeared in a similar bright red.

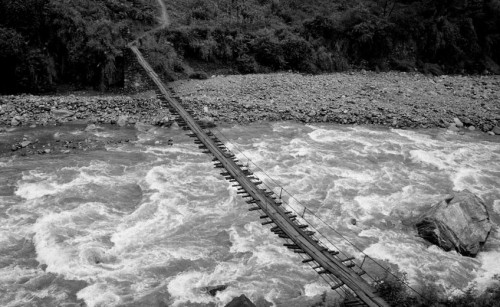

The eighth criterion stresses the significance of on-going geological processes of a site. In the case of the Namib Sand Sea, the formation processes began with the movement of enormous quantities of sand by major rivers flowing thousands of kilometres from the hinterland into the ocean for as long as time is remembered. The next extraordinary process is the ocean’s strong currents washing the sand back onshore. The desert wind has finalized the process by blowing the onshore sand further into the desert, creating the spectacular diversified formations of high sand dunes the world is seeing today. I had a vantage point on top of Big Daddy to observe the surrounding dunes and dried salt pans and could confirm the phenomenal result of the site’s ongoing geological processes.

Aside from the first two criteria which emphasize the natural beauty and geological processes of the Namib Sand Sea, the third, or nineth criterion, highlights the ongoing ecological process undertaken by plant and animal species in adapting their ways of life to survive and flourish in the harsh and extremely dry desert environment. Relying on fog as the primary source of water, the plants and animals have resorted to physical evolution over the years to endure under such limitations imposed on them.

Driving through the vast, arid plains, entering the Namib-Naukluft Park on the way to the desert area of Sossusvlei and also on the way back, I was amazed to spot several species of wildlife I didn’t expect to see in one of the driest places in the world. A herd of gemsboks, a subspecies of oryx antelope, I observed grazing unperturbed in a field of dry grass at the foot of a sand dune. Equally awesome was the sight of ostrich parents rearing their six chicks on the arid ground of the park as well as a Burchell’s zebra mare suckling her foal in the middle of the semi-desert environment. It looked like a normal day for a Southern Giraffe male roaming alone searching for food in the seemingly infertile land. I caught sight of a carnivorous black-backed jackal hunting in a field of tall grass and wondered what animals which dwelt there would fall prey and fulfil its hunger.

I was surprised but delighted to spot a raptor perching Adventure Southern Giraffe. on a tree in the middle of an isolated field. My local guide told me it was a pale chanting goshawk, a resident of the dry, open semi-desert that receives only 75 cm or less annual rainfall. The same thought I had with the black-backed jackal piqued my curiosity, wondering what could be the raptor’s prey. I learned from the guide that a goshawk hunted a variety of prey of small mammals, lizards, birds, large insects and even carrion when live prey became scarce. A goshawk prefers an open-ground habitat of dry semi-desert with perches that provide a vantage point to spot a prey.

Passing through an abundant pasture of dry grass in the park on my journey back to Windhoek, my driver stopped our vehicle on a tarmac road to let a large herd of springboks, a medium-sized antelope found mainly in Namibia, South Africa and Botswana, to cross the road. Both male and female have a pair of black, 35-to-50 cm-long horns that curve backwards. They feed on succulent vegetation, enabling them to survive without drinking water for years. The springbok is the national animal of South Africa, Namibia’s southernmost neighbour.

The tenth criterion requires the property to be outstanding in the conservation of an unusual and exceptional array of endemic species uniquely adapted to life in a hyper-arid desert environment. While trekking up the Big Daddy sand dune, I was fortunate to spot and quickly photograph a shovel-snouted lizard crawling close by before it disappeared under the sand. I was astounded to see how the lizard’s whole body immediately sunk below without a trace. The guide told me the dunes’ sand particles loosely join together, enabling most invertebrate animals living here to display rare behavioural adaptions like what I had just witnessed. Nature has provided these defenceless animals an efficient way to swiftly flee from their predators. The shovel-snouted lizard is also aptly called the Namib sand-diver.

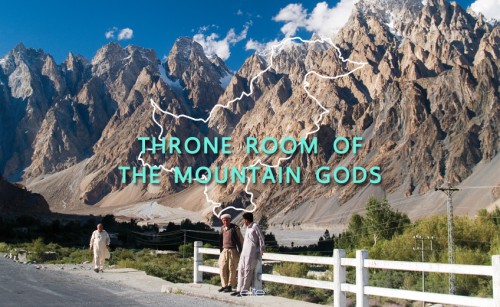

As we were driving toward the exit of the Namib-Naukluft Park, we passed one of the massive Naukluft Mountains’ peaks as we did as we entered the park. This time I had an opportunity to stop to photograph it.

Thus, ends my exploration of the Namib Sand Sea, Namibia’s second World Heritage Site. However, my adventure in Namibia will continue in the next issue of Elite+ with my visit to Etosha National Park in the northern region of Namibia.