How artist, anthropologist and ardent self-educator Cecê Nobre uses Kilombu, an invented world, to shine a light on disappearing cultures and build a better global community

Cecê Nobre sits at the bar at Sathon 11 Art Space, glancing from time to time at a near-finished mural spray-painted on the wall in the next room. It’s a rare down moment for the prolific artist. He furrows his brow, runs his fingers through his thick, curly hair, and takes a swig from a bottle of Beer Lao. “My mind as an anthropologist is all about collecting and analysing information,” he says. “I didn't go to school for art, so I watch other people, I pay attention to my mistakes.”

Cecê, as he suggests, is a self-taught artist who speaks with a fluency and self-awareness that betray his intellect as well as his loquacious character. Born in Brazil to a Paraguayan father and American mother, he spent his twenties shuttling between Rio de Janeiro, Paraguay and Washington, DC. “My parents kind of raised me as a Brazilian [even in the US]. As an adult, when I have to represent one country out of three, I choose Brazil,” he says. Now based in Thailand, he followed what can only he described as a circuitous path to Southeast Asia. Having left Brazil under less than ideal circumstances, he moved to Bangkok on a whim, believing that out of all the Asian cultures, it would be most similar to the cultures he knew in South America. And it was here that he sharpened his vibrant graffiti art and began to earn critical acclaim for it.

I sat down with Cecê to talk about that graffiti art, but quickly realized that his work can’t be simply typecast as street or graffiti art. In fact, Cecê himself defies categorization.

Over four hours, our conversation would stray from art to anthropology to auteurism. We talked about crime and punishment, prison systems and social order, topology and amateur cartography, agriculture and architecture, language and religion. He referenced the Guaraní, Rastafarians and Fulani. Burkina Faso and Borneo, North India and New Zealand. He is, to say the least, well read. But his knowledge of world cultures and societal issues, I would discover, are not the manifestation of an ambition too big to rein in, but rather the foundation of what might become Cecê’s life’s work – Kilombu. “I’ve had the idea of Kilombu for a while,” he tells me.“I’ve used that word in my art since 2008, but I thought of it more as a mental space – an idea or a feeling. Since 2015, I’ve turned it into a physical space.”

.jpg)

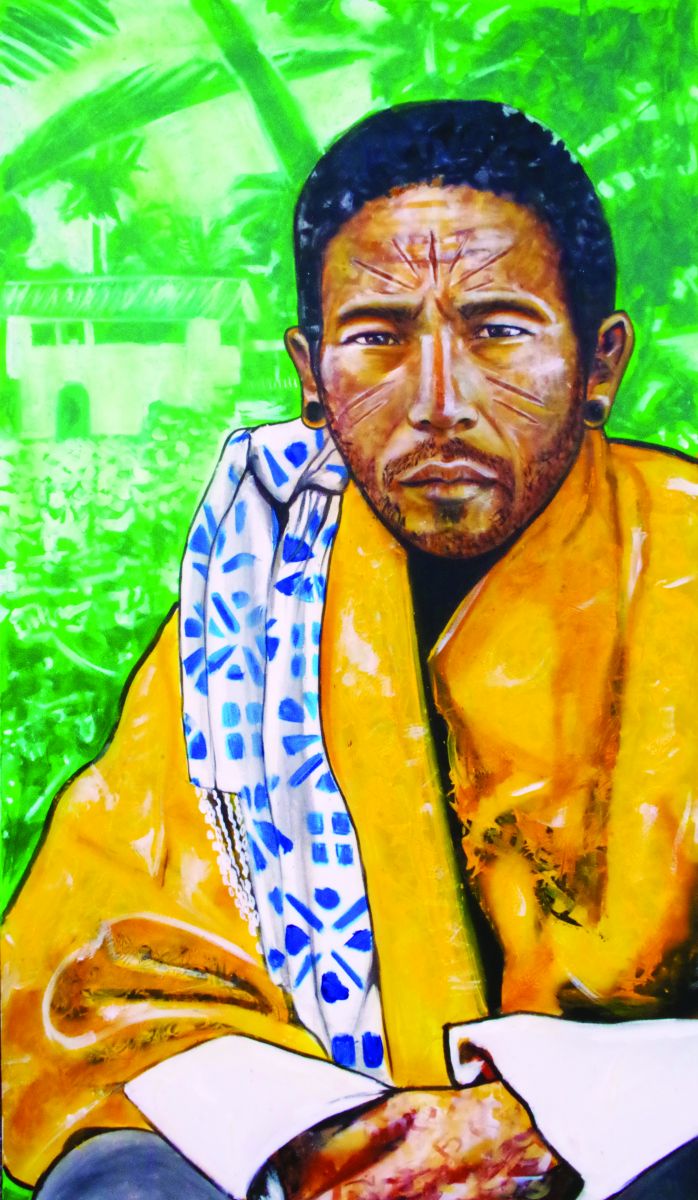

Kilombu, he explains, is a world of his own design – the world that appears in all his artwork, where all the characters he creates “live”, as it were. In Cecê’s Kilombu, the landscape appears agrarian and tropical, and its people look strangely familiar. The written language resembles Thai or Khmer, the spoken a pastiche of tongues such as Guaraní, Thai and Sango, a creole dialect native to the Central African Republic. Kilombu seems ancient (“I would like people to realize that one day our civilization will be ancient, too”), but in reality represents a theoretically possible future in which cultures from across the world have blended in so beautifully that racial differences have become less magnified, religion has lost its dogma and moral codes aspire to modesty. “I like the middle way in everything,” Cecê says

“Everybody is so distracted by things that entertain them,” he continues. “So I ask myself, ‘How can I entertain people while they are subconsciously being educated?’ I can use Kilombu to get people interested in anthropology, in terms of analysing culture. Rather than viewing cultures as boxed things – this is Thai culture, this is Chinese culture, and that's how it is – they can see that cultures can be more fluid, and they might analyse themselves for the first time.”

To draw viewers into his world, Cecê, who tags as Yik (meaning “curly” in Thai) and exhibits as Cecê, has employed an eye-catching combination of colours and multi-ethnic designs that bridge urban street culture, Brazilian Tropicalia and the politics of diaspora in murals and paintings. His characters stand out for their butterscotch skin tones, bright attire and the exotic script tattooed on their bodies, as well as the soft defining lines that Cecê has mastered with the spray can. These symbols are at once familiar and not. Many have been plucked from disappearing cultures, a carefully considered decision made by a self-described third culture kid.

“Tropicalia was making the Brazilian more European. I'm doing what they did, but instead of going European, I'm going subaltern, global southern, countries that were former colonies – third world, in other words,” he says. “I liked the idea that I could sew together all these different cultures that are disappearing or threatened. You look at the Guaraní, in 20 or 30 years, it could all be gone. I thought, 'How can I preserve it?' If I make this into a book or movie or game, people will internalize Guaraní. It's now entered the lexicon of the world.”

.jpg)

Using those subconsciously recognizable symbols and attention-grabbing colours as an entry point, Cecê has gradually incorporated new elements of Kilombu into his shows and expanded his art from graffiti murals to mixed media and products. For his show at Sathon 11, he presented necklaces adorned with heavy pendants. Each was inscribed with his invented language, Phasom.

“I want to work with craftsmen to make real relics,” he says. “[For this show], I went to China and worked with a Nakhi silversmith to make jewellery. The Nakhi is the only culture in the world that still uses hieroglyphics. Now I can incorporate some of that culture in Kilombu.”

He’s envisioned a society, developed its language and depicted its people, and yet his ambition suggests this is only the beginning. On a recent trip to Nigeria, a local artist listened as Cecê described his project and encouraged him to build on the world he’s created. “He told me to look at a room and consider what a table might look like, what kind of cutlery they might use, and so on,” he says. “Now I’m wondering what a menu might look like, a passport, a phone, how do they discipline their children, what are their holidays.”

Cecê might soon search for new media to expand the reach of Kilombu, too: movies, books, maybe even video games. And he hopes other artists will pick up on Kilombu and weave their own work into the world he has created.

“I got into street art because street art is ephemeral. You know, there’s beauty in watching society democratize your artwork, but I also don’t like the side of it that’s one-off, and I don’t like everything being so detached,” he says. “In the world today, everyone is so about themselves. I wanted to create a project that would force me to work with other artists and force the project to be out of my hands, where I don’t have full control of it.”

Not to mention, he admits, he might get bored of painting. “I might get tired of the limits of its communication. I also feel as I get older I’ll want more challenges.”

Whether those challenges come from giving other artists an opportunity to shape Kilombu or picking up a new skill, Cecê shows no sign of slowing down. Not even with a wife, a child and a full-time job as an art teacher to consider, nor his impending move to Phuket to work at the United World College, nor the possibility that Kilombu doesn’t catch on as he hopes it will.

“When I started painting, I was afraid to fail, of looking bad and what that would to do my self-esteem. Since then, it’s been a basis to help me get over my fears,” he says. “Art will teach you not to get discouraged.