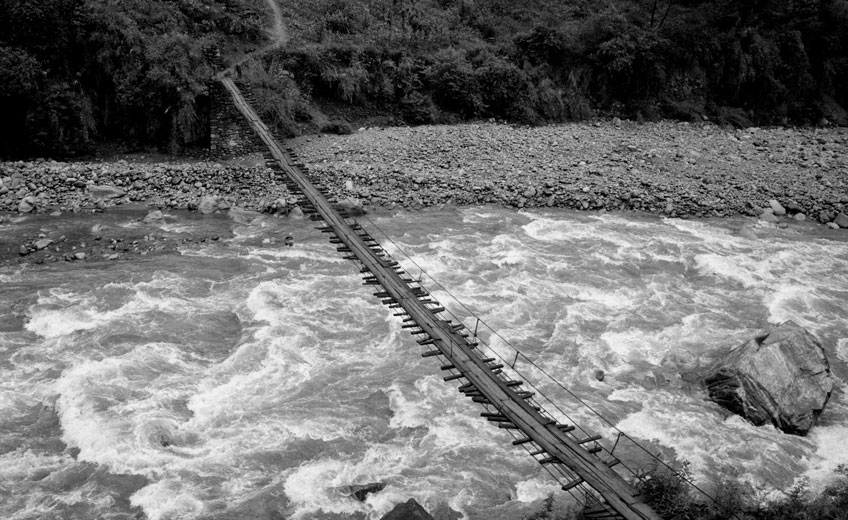

The engine suddenly died, causing my heart to almost stop beating. I knew the clutch of the car had a problem. Letting it out too quickly could kill the engine; releasing it too slowly could cause us to jerk forward, losing control. And as this bridge we were crossing was no more than two big logs across the creek, a few false degrees of the steering wheel could easily send us into the water.

Adding to our misfortune, I couldn’t feel where the wheels were on the logs. If I had managed to position the wheels right on the logs since the start of the crossing, the rest would have been easy. I would only have to make sure the steering wheel didn’t move, and we’d quickly be safe on the other side.

But this creek was the widest of those we had encountered. Now the engine had died in the middle of the bridge and I couldn’t even step out of the car to inspect the position of the wheels on the logs because there was no room to stand. I had to send my passenger friends on foot to the other end to guide me through. Any time they signalled the wheels were deviating, I took a deep breath to relieve stress.

Anyway, we made it across safely. Not long afterwards, we arrived at the Huai Nam Kaew forest protection station located deep in the eastern part of the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary. My watch said 10 minutes to 5pm. We had left Umphang at 10 in the morning. The drive had taken a long time for a distance of around a hundred kilometres.

Of course, driving on mountain dirt roads wasn’t new to me. Though I cannot call myself an experienced off-road driver, I feel more confident and safer driving through jungle than on roads where motorists are unpredictable and things are complicated. There are no traffic rules and no paved roads in the jungle, and no games. The challenges are deep creeks and steep hills, but those I can manage.

We had left Bangkok the day before in this 4WD borrowed from a friend. Two friends and I took turns driving to Umphang. Winding up mountains, we arrived at our lodge late at night.

The beginning of February in Umphang is cold. I stayed warm near the bonfire through most of the night. I believe that at night, fires are the only real representatives of the sun. Any fire comes from the sun. Humans make fires. But in fact, we only make copies of scientific elements and methods whose prototypes lie in nature.

Same as in life: however much self-determination we have, we still have to succumb to fate. Sometimes we accept it willingly, sometimes unwillingly.

[2]

The road from Mae Sot to Umphang was also very challenging. Not only was it twisting and narrow, but steep. A single steering mistake could mean death. Properly executed, the only reward was personal satisfaction.

Between Umphang and the forest protection station, the road was not that winding. It was a dirt road that slowly climbed up the mountains, then mostly stayed flat around 1,000 metres above sea level. It cut through thick forests, snaked through deserted plantations and wild grass fields.

Despite the various landscapes, I felt empty.

Many years ago, the eastern part of the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary was a major base of the embattled Communist Party of Thailand, of which I was a member. I lived here briefly during my early thirties, always relocating within the Thanon Thong Chai and Tanao Si ranges. I even thought of making this forest a station from which to fight against everything else I perceived as evil.

That was why returning to the forest felt like coming home.

Somphot Maneerat was a man in his early thirties, active now like I was over 10 years ago. He led the pioneer forest ranger team that had turned the base of the leftists into a wildlife sanctuary in 1988. That was why he loved and was so protective of the land. Usually visitors were not allowed in the area and could only stay around the sanctuary headquarters in Ka Ngae Khee. But because he thought of my friend as an older brother, or he knew I loved the green as much as he did, or a combination of the two, Somphot permitted us to go to the Huai Nam Kaew camp, the farthest point in the southeastern section of the sanctuary. There were no roads beyond this.

It was a misunderstanding that had brought us here. I thought this Huai Nam Kaew was the same as the Huai Nam Kaew creek along the trail we the communists had once walked. That trail wound across mountains from Mae Chanta to the mouth of Ong Tang creek, closer to the lake above Srinakarin Dam. On that trail was a huge waterfall I wanted to revisit – tall, multi-level falls with crystal clear blue water.

So Somphot’s Huai Nam Kaew and my Huai Nam Kaew were two different places. His was closer to the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary (northeast of the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary) and was probably the downhill trail I had walked to give myself up to the government. I don’t think any ranger teams have been there yet.

Somphot, who wanted to learn more about the forest in his care and help in my wish to revisit the area, showed me a detailed contour map of the area. As soon as I saw it, I knew roughly what kinds of roads to expect.

I remembered that we the communists had waded through the Mae Klong or Khwae Yai rivers on our way east. Not too long after the river, we crossed the Kakata creek and started to climb a steep mountain. From a rest point on the mountain, we turned right on the trail that led to the Khwae Yai river, passing numerous sheer cliffs. The Huai Nam Kaew creek I wanted to revisit was somewhere on this trail. The waterfall was not too far from the creek and had to merge with the Mae Klong river somewhere oblique to the mouth of the Dong Wee creek originating in the western part of the wildlife sanctuary.

I explained the topography and the landscapes along the trail to Somphot when we first met so he could locate it. But it turned out the area hadn’t been explored by any ranger teams, including Somphot.