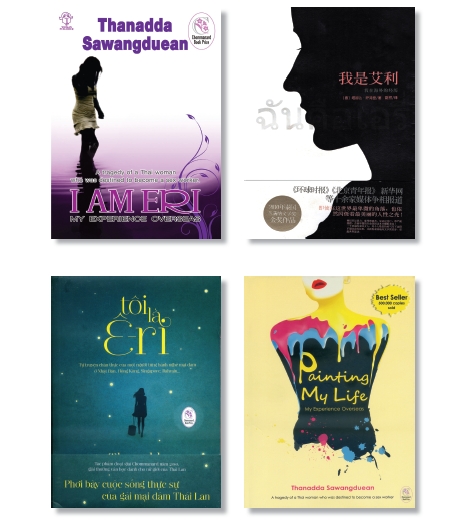

“Highlights from around the globe: A former prostitute has won a top Asian literary prize for her autobiography. ” This snippet, regarding the book I am Eri: My Experience Overseas by Thanadda Sawangduean, was written by Lucy Holland-Smith and appeared in the top corner of the homepage for the London Book Fair.

Since the announcement of that work as the Chommanard Book Prize winner on December 21, 2010, the story of Ms Thanadda, or Eri, has been told by word of mouth, in the news and on blogs around the world. Three successful sequels have followed. When her story comes up today, many wonder about her daily life, perhaps even whether she has re-entered the vicious cycle of the oldest profession.

Elite+ had the opportunity to interview her personally and find out more about the individual behind the books.“I’m working every day on a new manuscript,” Ms Thanadda said. “My career now is as a full-time writer. I don’t have other income to support myself. After my first book, I Am Eri: My Experience Overseas, which became a best-seller in Thailand, I was approached with various offers of work. But I only agreed to one, and that’s as a columnist for Plak, a weekly Thai newspaper.

“I’m grateful to Praphansarn, which has published every one of my books from the beginning,” she said with a smile. “The various editions of the four titles have helped me survive up to now. There’s no need to change careers or go back to the realm of prostitution.

“The first book is still my greatest pride. The Chommanard Book Prize is based on a strong belief in the talent of Thai women. The book was then published in other languages, such as English, Chinese, Taiwanese, Vietnamese and others.” We spoke in the evening at the end of July, as the dim light of sunset cast shadows over dinner. The photographic team invited us up the studio after the meal.

“What’s your lifestyle like, besides daily writing?” My questions grew more assertive as we followed the photographic team. “I heard you went to study hairstyling and manicure.”

She smiled. “I think you misunderstood. I didn’t want to practise hairstyling and manicuring in order to change careers. After I won the Chommanard Prize many people offered to support me in various ways. But I chose to take a free shortcourse for dressing fingers and hair, because I’m a woman by nature. It wasn’t an expensive course, so I felt better taking it since I don’t want to owe anyone too much. Actually, I’ve already forgotten what I learned.” My curiosity was piqued when she added: “Do you want to know what my main interest is, besides writing?

“I was a prisoner in many countries, such as in Thailand, Japan, Singapore and even in the Middle East. It’s hard for other people to understand a prisoner’s life.”

She paused before continuing. “I was persuaded by Princesses Patchara Kittiyapa, daughter of His Royal Highness the Crown Prince, to join a project call ‘Inspiring’. This was connected to one of my own interests, which is to be a source of inspiration for Thai prisoners. She invited me to talk to inmates at Bang Kwang prison. I agreed because, as a former prisoner, I know what they are feeling and how to communicate with them. I know they don’t really want a religious sermon or a yoga lesson; they need humour. Many volunteers can’t reach the prisoners because they don’t have inside experience like me, and they don’t understand their basic needs.

“Thai prisoners who don’t have people sending them money are the lowest class in jail, especially in women’s prisons. If they have their monthly period, for example, they just have to wear dirty clothes because they can’t afford sanitary pads. In contrast, if a prisoner comes from a rich family, she’s treated differently, like a big boss in the jail. They even open some businesses inside to exploit the poorer class, such as selling overpriced soap and shampoo, and the poorer ones have to pay for it by doing dirty jobs for the upper class.

“After I finished the ‘Inspiring’ project, I wanted to continue visiting prisoners in my own way. I did this informally, not through a big network. At my own expense I visited prisoners at 12 places in two years. I was also invited to lecture at around two places a week, but I gave my lecture fees to the poorer prisoners, especially the lonely ones who had no relatives supporting them.

“While I did this, some organizations approached me, but their conditions for supporting prisoners were all false. I didn’t want to make any profit off of prisoners who shared my unlucky fate. Anyone who wants to join me in helping them, please treat prisoners as human, and don’t create projects that try to earn money from them like they’re some kind of merchandise.”

Ms Thanada asked our team to move from the air-conditioned room to the balcony. While smoking a cigarette, she had us look at the sky. Night had fallen, and many stars shone. Eri told us how happy she was working for prisoners. With the right mentality, anyone could be a star for them.

As she left, she said: “I can earn a living from my second book, I Am Eri: My Experience in Jails. The title is also a reminder for me never to forget that charity for prisoners is like charity for myself.”

Good night, Eri. You are my elite.