I’m not in the habit of starting the day with shots of rice wine. But on my first return visit to southeast Guizhou Province in 25 years that’s how the day started.Young Miao minority women dressed in embroidered linen jackets and pleated skirts – some wearing ornate silver crowns – foisted them upon me in brass bowls on the high-street of Danzhai Wanda Village in a grand welcoming ceremony.

Obviously, not everyone gets this welcome, but this little-known corner of China sees very few foreign visitors. There was also the fact that I was village mayor for a week, as part of a rotating programme that invites travel writers, bloggers and internet celebrities to spend a week in Danzhai Wanda Village and promote a minority region of China that until recently was so inaccessible that it had little to no tourism.

Southeast Guizhou Province is known in Chinese as Qiandongnan, or to be precise, Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, a reference to the fact that more than 70% of the population are either Miao (known in Thailand as the Hmong) or Dong (also known as the Kam).

For much of China’s turbulent 20th century the Miao and Dong have lived in the misty mountains and valleys of this region with no roads and no electricity, for the most part isolated from the outside world. That only began to change over the past decade, as China’s vast infrastructure surge finally rolled into Guizhou Province, bringing high-speed rail to the city of Kaili and highways to county seats throughout the region.

That said, unlike neighbouring Yunnan Province, which was discovered by foreign tourists and travellers in the 1980s, Guizhou remains difficult to navigate, with little public transportation other than county-seat to county-seat buses. As visiting mayor, I had the good fortune of having my own driver – a somewhat surly Mr Chi, who lightened up as the days passed and we cruised from one minority village to another.

But first I explored Danzhai Wanda Village, site of a CNY 2 billion (US$284.5 million) corporate social-responsible (CSR) programme by China’s Wanda Group that has seen the construction of a vocational college, a tourist village and a poverty-relief fund to address the county’s long-term, medium-term and short-term developmental needs.

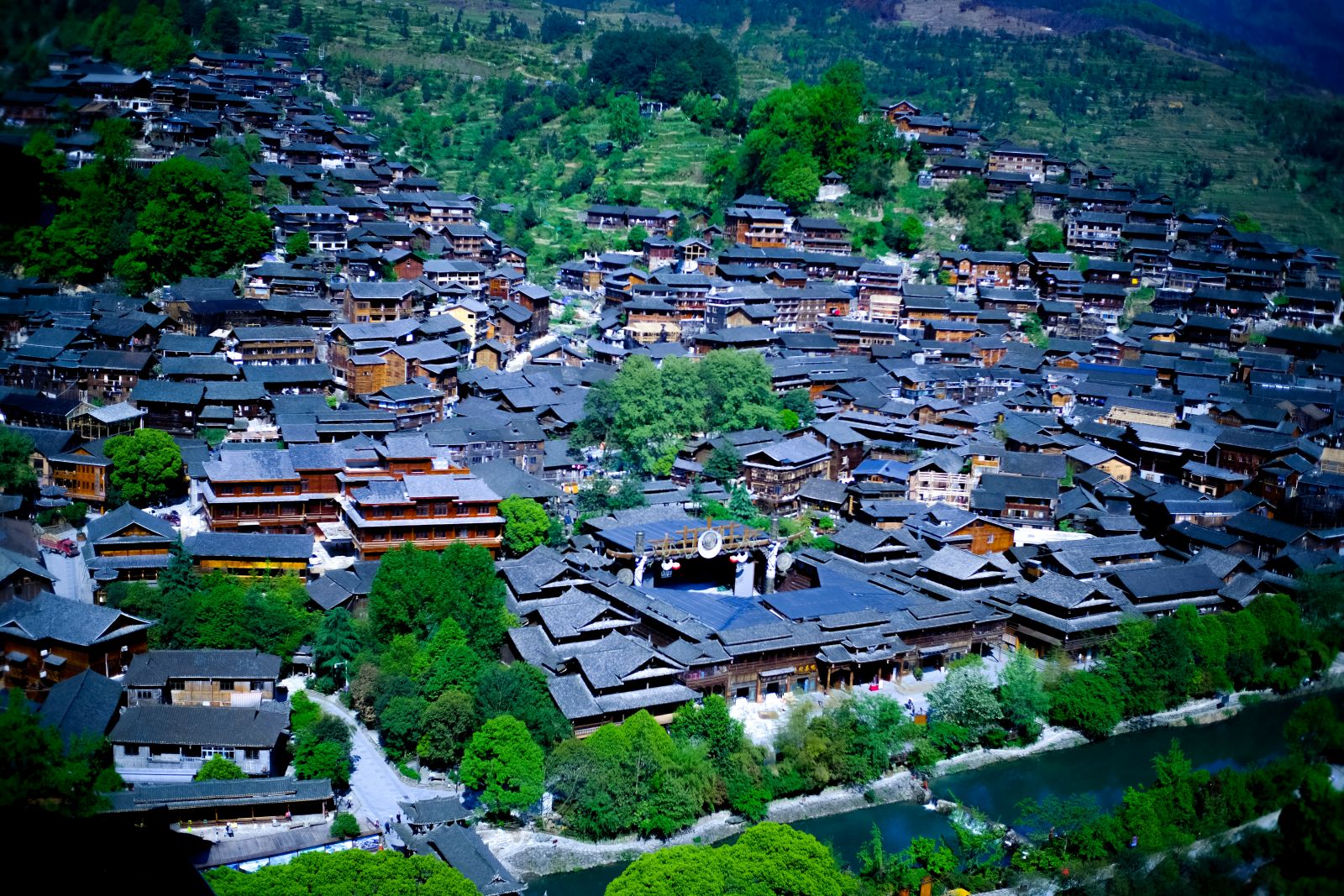

Danzhai is not without its charms, but to call it a traditional Miao village would be an exaggeration. No more than several years old it consists of one shop- and restaurant-lined, slate-paved high street with three village squares, where Miao minority dancers perform with enthusiasm on a nightly basis. One could be cruel and label it “fake”, but the fact is the that the recently built village serves as a market town for Miao villagers dwelling in habitations scattered around the nearby rolling hills.

The village was lively too. Despite the drifting wintry fog and the drizzling rain, Danzhai’s high street thronged with Chinese tourists, as snaking processions of Miao in full traditional attire paraded from one village square to the next.

On the second day, I began to feel as if I was witness to something rare in China – a full-blown resurgence in minority pride. I began to wonder whether this could be sustainable, given the relentless onslaught of mainstream Han media – soap operas, movies, shopping apps and homegrown YouTube lookalikes.

Huang Xiaohai, a deprecating 61-year-old photographer who has been documenting Miao minority culture for more than 25 years and who agreed to come to my hotel and show me his photographs, admitted he was worried. As I looked at some of his favourite images – a curated selection from what he claimed was a total of more than 100,000 – I asked him what he was worried about.

“It’s difficult,” he said. “So many of these young Miao people went to Guangdong and other parts of east-coast China to work and make money, and it’s changed them. Now they’re returning because there are roads and electricity and internet, but they have to relearn their culture. If you look closely when they’re traditionally dressed, you’ll notice that most of them have abandoned their traditional wooden shoes, and often, when the women are dancing, they’re taking selfies of themselves as they do so.”

He frowned and shrugged. “But they are returning, and they have opportunities nobody could have dreamed of 10 years ago. We just have to proceed cautiously, not too quickly, and ensure that when we help them bring their products to market and lift their living conditions, it’s not at the cost of their traditional culture.”

I was eager to find others who could provide some insight into the transformations that were taking place in this rustic, minority slice of Southwest China, which led me to a charming rustic homestay and social enterprise called Village Story.

Over lunch beside a pond, surrounded by forested hills, a 44-year-old former marketing executive from Beijing told me how he had decided to devote his life to bringing commercial opportunities to makers of Miao and Dong traditional crafts through bricks-and-mortar stores and online sales.

He Bowen is one of Village Story’s three partners. Together, they engage with more than 30 villages – thousands of villagers – training them to improve the quality and efficiency of manufacturing traditional handicrafts.

He described his first visit to Danzhai in 2010, a visit that changed his life: “It was dark, the road was long, but when I got here, the lights were on and I was met with so many beautiful traditional products.”

I asked him whether he thought that, by taking Miao and Dong traditional handicrafts to the China-wide market, Village Story was having a positive impact. He replied that the positive impacts were manifold.

“It’s an opportunity for the villagers to feel proud of traditions that until very recently were unknown outside this region,” he said, adding: “But there’s more to it than that. There’s another big positive change. The women start to make money every month, while the men make money just once a year during harvest season, so the men have started to depend on the women for income and that has made the women become more confident.”

It was a refrain I was to hear repeatedly as I travelled around Qiandongnan, touching down in villages that could only remember one or two previous foreign guests.

One of those was Guiliu, a Dong minority village with wooden “wind and rain bridges” and soaring “drum towers”. In Guliu, Yang Hui, a Dong primary-school teacher with an easy smile and unassuming confidence, told me, “When I came here in 1991, there was no road, no electricity. If the local people wanted to go market, they had to walk to the county seat, which was four hours away. The girls didn’t attend school. That’s all changed. All the girls get an education, it’s 30 minutes to the market at the county seat and it’s even possible to shop online using mobile phones.” She assumed a thoughtful expression and added, “But this is still a Dong village.”

When I left Qiandongnan to fly back to Bangkok from the Guizhou provincial capital of Guiyang, I had the overwhelming feeling that I’d been witness to something remarkable – a re-flourishing of ethnic identity and pride that was also improving livelihoods.

Such stories are rare and – amid all the bad news that comes out of China – a reminder that a country of 1.4 billion people cannot be encapsulated in any single story. Qiandongnan has its own unique story that deserves a bigger audience and that can only happen with more visitors.