My first trip in 2017 took me to central India visiting four national parks — Keoladeo, Satpura, Pench and Kanha — and two cultural World Heritage Sites — the Buddhist monuments at Sanchi and the Bhimbetka rock shelters. I flew from Bangkok to Delhi, stayed overnight, and continued by car the next morning to Bharatpur, Rajasthan, location of the Keoladeo National Park, or Keoladeo Ghana National Park, inscribed as a UNESCO natural World Heritage Site in 1985.

Despite its relatively small size of 29 square kilometres, Keoladeo is undoubtedly qualified under the criteria (x) having contained “the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation” to be designated a World Heritage Site. Its uniquely diverse landscape comprises wetlands, woodlands, grasslands and woodland swamps, and is home to more than 350 species of birds and also many species of fish, reptiles, amphibians and mammals. The park is regarded as one of the richest bird areas in the world, where thousands of migrating birds make an annual winter visit to breed.

We planned to visit Keoladeo in the afternoon of the first day and continue the whole second day. It was my first experience visiting a national park with three options in touring the park — walking, renting a bicycle or using a rickshaw service. My party of five decided to hire three rickshaws to ride on as well as carry our photographic equipment. The additional bonus was that each rickshaw driver was knowledgeable about the birds of Keoladeo and helped our local guide in spotting bird species and providing additional information.

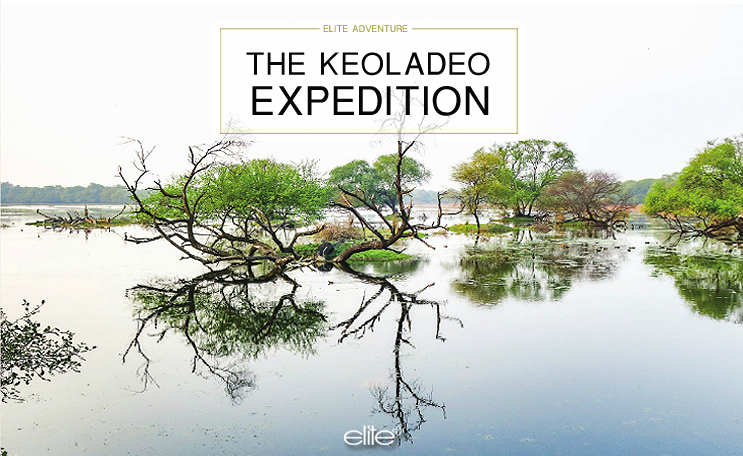

We started our tour of Keoladeo after lunch and had only three hours before the gate closed at five. Our local guide therefore led us to a large wetland near the main gate. It took us 10 minutes by rickshaw to get there. We walked along the tree-covered path which led into the middle of the wetland. The scenery around us was the first evidence of why Keoladeo has been awarded the World Heritage Site status. I marvelled at the amazingly clear water of the wetland as it produced picturesque reflections of the trees that grew on several islets in the wetland.

My visit was planned to coincide with the migrating season of thousands of birds and ducks wintering in Keoladeo. I stood on the bank of the wetland trying to identify many species of waterbirds and ducks on tree and feeding in the water in front of me. Several species were familiar — common coot, common teal, spot-billed duck, northern shoveler, Eurasian spoonbill, grey heron, bar-headed goose, pied kingfisher, Oriental darter and little cormorant. I relied on the local guide to identify the unfamiliar species — bay-backed shrike, little grebe, red-crested pochard and gadwall.

Three hours went by fast, and we had to leave the park just before the gate closed, looking forward to spending the whole next day of birding and photographing in Keoladeo. The park is open daily from 8am to 5pm.

After breakfast, we arrived at the main gate of Keoladeo at 9am with the same local guide and were greeted by the same three rickshaw drivers from the day before. It was a pleasant ride on the main park road into the interior of the park passing the turn-off we took yesterday to the nearest wetland. The road cut through several wetlands, woodlands, dry deciduous forests and swamps. It was an unbelievable sight of spotting different species of birds wherever there was water. After a 10-minute ride, the rickshaws stopped at a spot where we got off and started walking with our cameras ready.

The guide pointed to the left side of the road at a group of islets, where hundreds of painted storks, a near threatened species, formed a large colony and made nests on the trees. The painted storks are endemic to Asia from India in South Asia to the countries of Southeast Asia. Their habitats are freshwater wetlands, canals and crop fields. They are medium-sized storks standing 93 to 102cm tall with a wingspan of 150 to 160cm and a weight of 2 to 3.5kg. They feed on small fish, frogs and occasion-ally snakes.

The next large bird, actually the largest bird I saw at Keoladeo, was great white pelican which are distributed widely in Eastern Europe, Africa, India, Pakistan, Nepal and Myanmar. I sighted a flock of about 30 great white pelicans feeding in one of the wetlands before flying to another spot. This species of pelicans is 150 to 175cm in length with a wingspan of 220 to 350cm and a weight of 5.5 to 15kg. The males are larger than the females. They feed mainly on fish, and also frogs, crustaceans and small birds.

The ibises I spotted and photographed at Keoladeo were black-headed ibis and glossy ibis. I saw two black-headed ibises wading in a shallow wetland to feed on fish, frogs and other aquatic animals. They were about 75cm in length. A glossy ibis I sighted later in another wetland was smaller, with the length of 55 to 65cm and a wingspan of 80 to 105cm. Because of its long curved bill, the glossy bliss has another common name: the black curlew.

Keoladeo is also a favourite wintering ground of migrating geese and ducks from Central Asia and China. I found a covey of eight bar-headed geese, also known as Indian geese, on an islet in a wetland. They were mid-sized geese, with a length of 71 to 76cm, a wingspan of 140 to 160cm, and a weight of 1.87 to 3.2kg. The bar-headed goose was once classified by the IUCN (International Union on Conservation of Nature) as near threatened because of continuing population decline from hunting, egg collection and habitat destruction.